FORT GREENE

Geographic Setting

Bounded by Atlantic Avenue to the south and Flushing Avenue to the north, Vanderbilt Avenue to the east, and a western line running north along Flatbush Avenue between Atlantic and DeKalb Avenues, Ashland Place between DeKalb and Myrtle Avenues, and Prince Street between Myrtle and Flushing Avenues, Fort Greene stands as one of Brooklyn’s most historically resonant and architecturally distinguished neighborhoods. Rising gently above the surrounding city, it occupies the elevated ridge once known as Cumberland Hill, offering views toward the harbor and Manhattan skyline.

Today, Fort Greene is defined by its tree-lined streets, 19th-century brownstones, and cultural landmarks that have shaped generations of Brooklyn’s artistic and civic life. The neighborhood centers on Fort Greene Park, a 30-acre landscape designed in 1867 by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the same duo behind Central and Prospect Parks. Radiating from the park’s perimeter—along Lafayette Avenue, Cumberland Street, South Oxford Street, and Willoughby Avenue—stretch blocks of dignified Italianate, Greek Revival, and Second Empire rowhouses, their stoops shaded by towering London plane trees. To the south and west, the district blends seamlessly into the cultural hub of the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) and the redevelopment zones surrounding Atlantic Terminal, while to the north, the industrial edge along Flushing Avenue borders the Brooklyn Navy Yard, a reminder of the area’s historic connection to labor and production.

Etymology and Origins

Fort Greene takes its name from the Revolutionary War fortification built on this very hill in 1776, one of several defensive works erected by General Nathanael Greene during the Battle of Long Island. The original earthen fort—later rebuilt for the War of 1812—commanded sweeping views over Wallabout Bay, where thousands of American prisoners perished aboard British prison ships anchored offshore. Their remains, interred beneath the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument at the park’s summit, lend the neighborhood its solemn historic weight.

Through the early 19th century, this area was rural woodland and pasture belonging to Dutch-descended farming families. The name “Fort Greene” first appeared in maps of the 1820s, but it was the Navy Yard’s expansion (1801 onward) and the subsequent demand for nearby housing that triggered its transformation from farmland into an urban neighborhood.

The Neighborhood

19th Century: From Fortified Hill to Brownstone District

Development accelerated after the opening of Fulton Ferry (1814) and the incorporation of Brooklyn as a city (1834). By the 1840s, streets were laid, and grand homes rose along Cumberland, Clermont, and Vanderbilt Avenues, attracting merchants, shipbuilders, and professionals who sought proximity to the Navy Yard. The neighborhood’s elevated topography—considered healthful and scenic—earned it the nickname Brooklyn’s Hill of Health.

The 1847 construction of Fort Greene Park, initially called Washington Park, established the area’s centerpiece. Designed by Olmsted and Vaux two decades later, the park’s meadows, promenades, and central hill became a model for civic green space. Around it, rows of brownstones and brick houses multiplied, built in Italianate and Greek Revival styles with high stoops, tall windows, and ornamental cornices.

By the 1870s, Fort Greene had matured into one of Brooklyn’s most fashionable residential quarters. Churches such as Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian (1857) and Queen of All Saints Roman Catholic (1913) anchored the community, while schools, social clubs, and small theaters lent it cultural vitality. Yet, like neighboring Brooklyn Heights and Clinton Hill, its genteel reputation rested upon the prosperity of Brooklyn’s mercantile class, whose fortunes rose with the harbor trade.

Early–Mid 20th Century: Decline and Resilience

The 20th century brought dramatic shifts. As industrial employment expanded, the brownstone streets near the Navy Yard filled with working-class families and newly arrived immigrants. The opening of the Manhattan Bridge (1909) and subway extensions to Atlantic Avenue made Fort Greene more accessible, but also encouraged wealthier residents to move farther out. By the 1930s, many of the once-grand homes had been subdivided into rooming houses or small apartments.

The Great Depression and wartime mobilization intensified the area’s socioeconomic contrasts. The Navy Yard boomed during World War II, employing tens of thousands, but the postwar closure of factories and shipyards in the 1950s and 1960s triggered disinvestment. Urban renewal programs reshaped large swaths of Fort Greene: public housing complexes such as Whitman Houses (1944), Ingersoll Houses (1944), and Lafayette Gardens (1955) replaced deteriorated blocks, altering both the neighborhood’s skyline and social fabric.

During this era, Fort Greene became home to a significant African American community, part of the broader migration that transformed central Brooklyn. Churches, jazz clubs, and civic organizations thrived, even as poverty and neglect grew. Notable residents included Richard Wright, Ruth Brown, and later Spike Lee, whose films—especially Do the Right Thing and Crooklyn—immortalized Fort Greene’s complex beauty and community resilience.

Late 20th Century: Renaissance of Culture and Architecture

By the 1980s, the pendulum began to swing toward revival. Artists, writers, and professionals—drawn by the neighborhood’s architecture, proximity to Manhattan, and affordable rents—began restoring brownstones and reactivating cultural spaces. The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), founded in 1861, became the anchor of this creative renaissance, evolving into the centerpiece of the BAM Cultural District, which soon attracted institutions such as the Mark Morris Dance Center, BRIC Arts Media House, and the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts (MoCADA).

Meanwhile, block associations organized to preserve the neighborhood’s historic integrity. Their efforts culminated in the designation of the Fort Greene Historic District in 1978, protecting over 700 buildings and ensuring the survival of one of America’s most cohesive 19th-century streetscapes.

The diversity of the community—long a hallmark of Fort Greene—remained remarkable: African American professionals, Caribbean families, artists, and newcomers coexisted in a neighborhood that balanced bohemian energy with historic gravitas. Cafés and small theaters along DeKalb and Lafayette Avenues became local institutions, while Fort Greene Park, long a site of rallies and festivals, regained its role as Brooklyn’s green commons.

21st Century: Gentrification, Growth, and Cultural Legacy

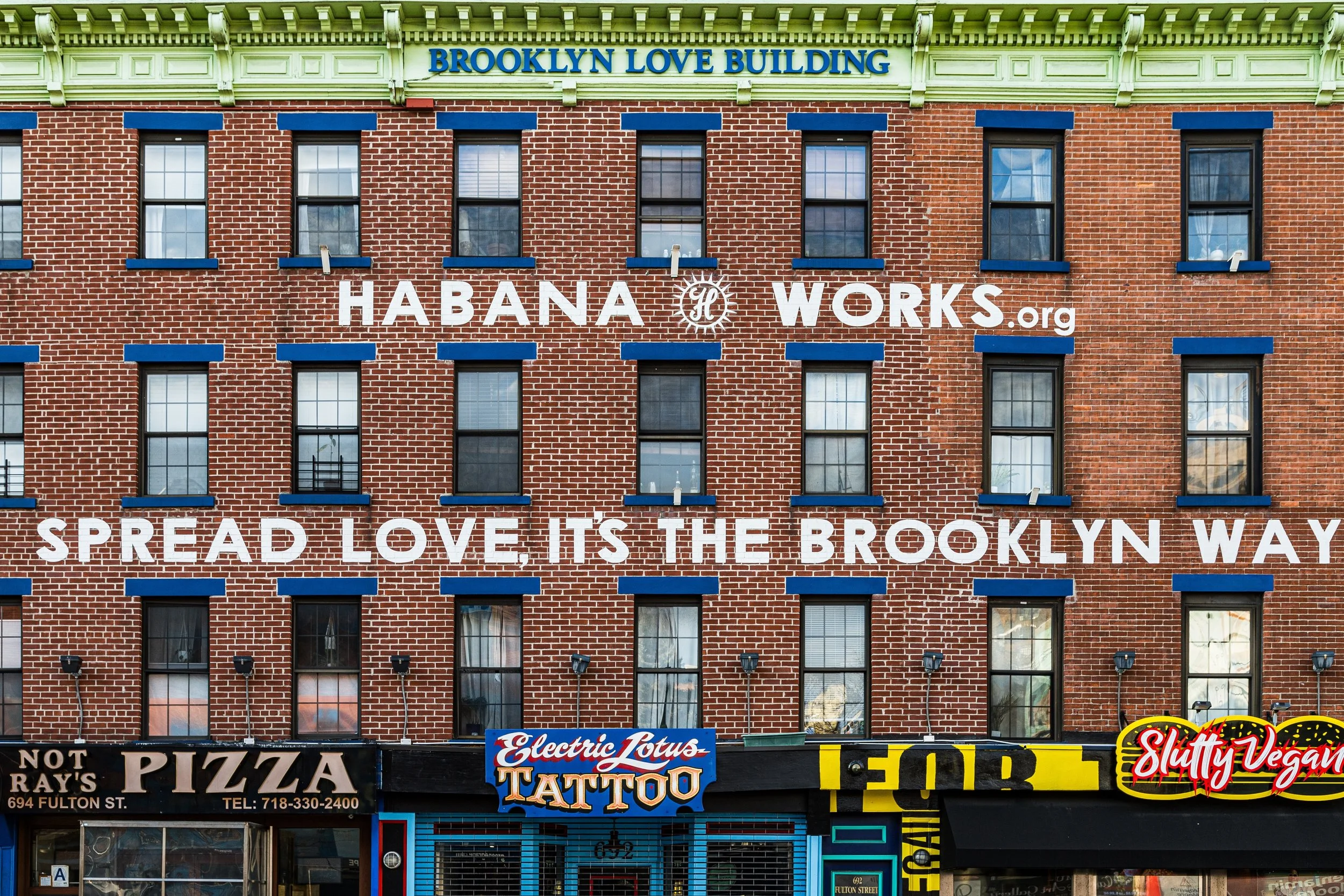

In the 21st century, Fort Greene has become one of Brooklyn’s most desirable addresses, its architectural beauty and cultural pedigree drawing new waves of residents. The BAM Cultural District now extends to Ashland Place, Lafayette Avenue, and Fulton Street, integrating performing arts venues with high-rise residential and mixed-use developments such as The Ashland (2016) and 300 Ashland Place (2017).

While this renewal has brought economic vitality and world-class culture, it has also intensified concerns over displacement and gentrification. Longtime residents—many of them African American and Caribbean families—have faced rising property taxes and rental pressures. Community organizations continue to advocate for affordability, cultural inclusion, and the preservation of Fort Greene’s distinctive social fabric.

Despite the influx of capital and change, the neighborhood’s essential character endures: the stately brownstones, the canopy of elms over Lafayette Avenue, the hum of the Saturday Fort Greene Greenmarket, and the sight of children playing beneath the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument. The contrast between the quiet park blocks and the cultural bustle around BAM defines the rhythm of life here—anchored in heritage, open to reinvention.

Spirit and Legacy

Fort Greene’s legacy is one of artistry, activism, and endurance. From a Revolutionary fort to a 19th-century enclave of refinement, from a mid-century crucible of struggle to a 21st-century nexus of art and diversity, it embodies the full arc of Brooklyn’s story. Its layered identity—Black and white, historic and avant-garde, residential and cultural—has made it a model of urban evolution that neither erases nor forgets.

New York City

Use this custom Google map to explore where every neighborhood in all five boroughs of New York City is located.

The Five Boroughs

One of New York City’s unique qualities is its organization in to 5 boroughs: Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, The Bronx, and Staten Island. These boroughs are part pragmatic administrative districts, and part vestiges of the region’s past. Each borough is an entire county in New York State - in fact, Brooklyn is, officially, Kings County, while Staten Island is, officially Richmond County. But that’s not the whole story …

Initially, New York City was located on the southern tip of Manhattan (now the Financial District) that was once the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. Across the East River, another city was rising: Brooklyn. In time, the city planners realized that unification between the rapidly rising cities would create commercial and industrial opportunities - through streamlined administration of the region.

So powerful was the pull of unification between New York and Brooklyn that three more counties were pulled into the unification: The Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island. And on January 1, 1898, the City of New York unified two cities and three counties into one Greater City of New York - containing the five boroughs we know today.

But because each borough developed differently and distinctly until unification, their neighborhoods likewise uniquely developed. Today, there are nearly 390 neighborhoods, each with their own histories, cultures, cuisines, and personalities - and each with residents who are fiercely proud of their corner of The Big Apple.