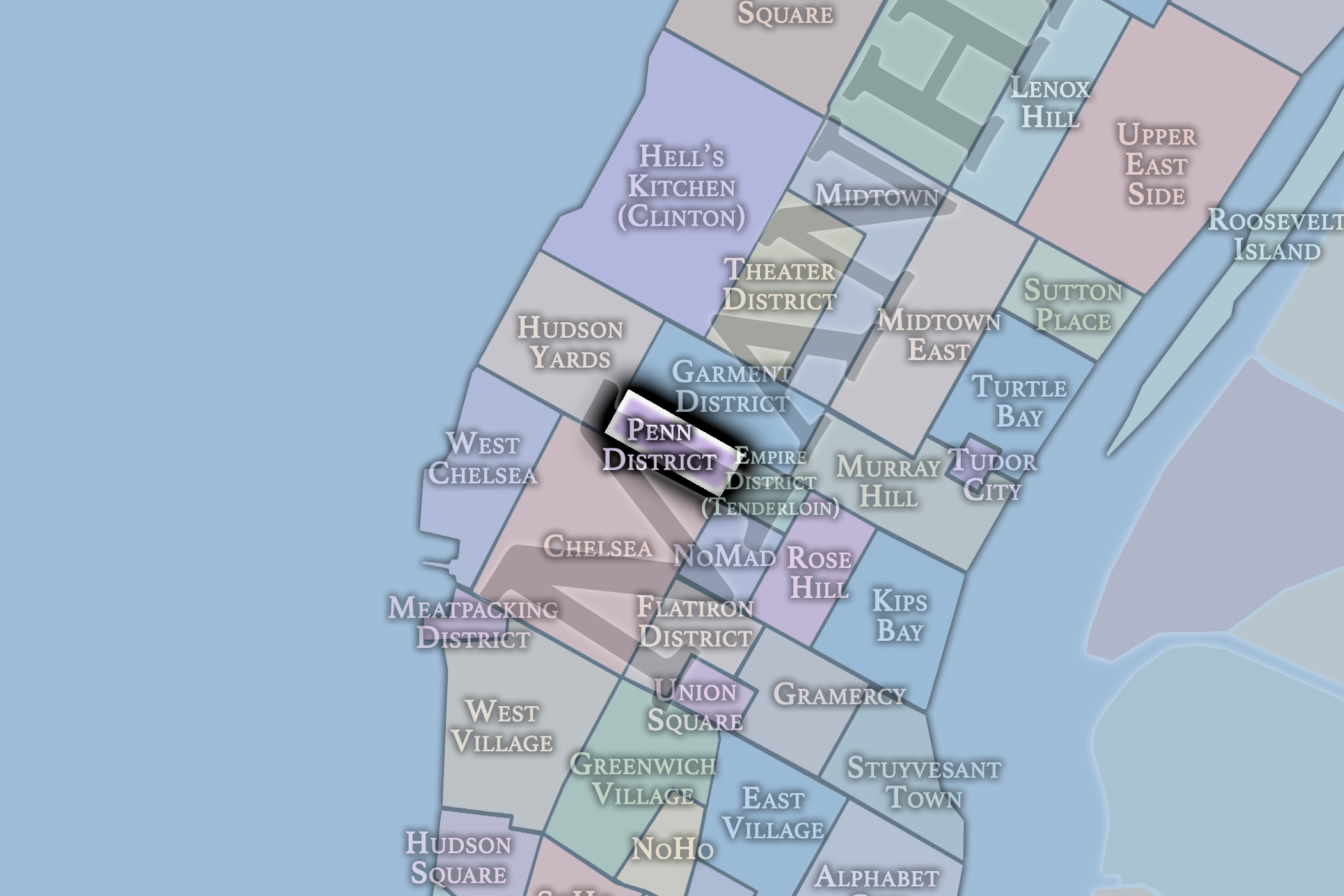

(Midtown South)

Manhattan

The End of “Midtown South”

(And Why We’re Excited to Redefine It)

For decades, the area between 30th and 34th Streets, from Madison Avenue to 9th Avenue, was the city’s favorite "shrug" of a neighborhood. It was a sprawling “catch-all” for disparate elements that stretched from Hell’s Kitchen to Madison Avenue.

Labeled generically by planners and real estate agents as Midtown South, it was the place you either attended raucous events at Madison Square Garden, scuttled through underground tunnels to catch a train, or where you bought a wholesale rug before heading somewhere with more "soul."

But as of 2026, this generic, umbrella label has run its course.

New York City doesn't just "renew"—it reveals. And thanks to the striking redevelopment underway and already completed in and around Penn Station and the Moynihan Train Hall, Midtown South has effectively revealed - and evolved into - two very different districts.

By leaving the “Midtown South” moniker behind, we are embracing a cartography that acknowledges the forward momentum of the city, and emphasizes the divergent personalities of these two “new” city neighborhoods.

Meet the two new neighborhoods that are redefining Midtown South:

1. The Penn District:

The Distinction: The renovations and rejuvenations happening east of 6th Avenue.

The Boundaries: 6th Avenue to 9th Avenue; 30th to 34th Street.

The Vibe: High-speed, high-tech, modern, and sun-lit.

The Spirit: If you’re looking for the future of New York’s infrastructure, you’re standing in it. The Penn District has shed its "dour" underground reputation for a new identity as a world-class transit campus.

The Highlights: Between the majestic Moynihan Train Hall and the newly reskinned glass towers of PENN 1 and PENN 2, and the modernized Madison Square Garden, the district is now a landscape of "superblocks," public plazas, and vertical steel. It’s the neighborhood that never stops moving because it’s literally built on top of the tracks that keep the city alive.

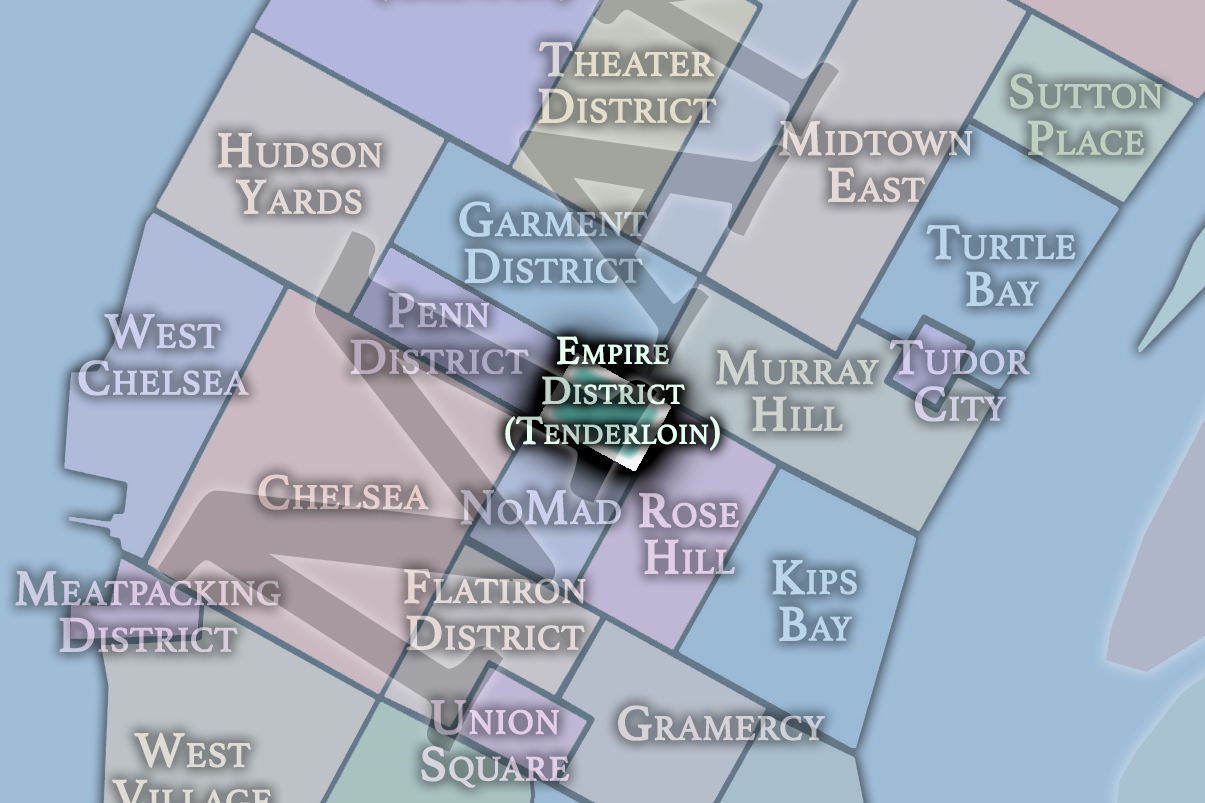

2. The Empire District (Tenderloin):

The Distinction: The legacy of a gilded age anchored at 34th Street and 5th Avenue.

The Boundaries: Madison Avenue to 6th Avenue; 30th to 34th Street.

The Vibe: Architectural grit and Gilded Age glamour.

The Spirit: Cross Sixth Avenue and the world changes instantly. This is the "pedestal" of the Empire State Building, a neighborhood of masonry canyons and secret histories.

The Highlights: This is the heart of the old Tenderloin, where the "Cradle of Pop" survives in the landmarked buildings of Tin Pan Alley on 28th Street. While the Penn District looks forward, the Empire District (Tenderloin) holds on to Manhattan’s mercantile soul, housing the city's legendary wholesale perfume and rug trades within the ornate stone of 19th-century hotels.

A Note For Those Still In Search of a Midtown South:

While the city evolves into the Penn and Empire Districts, the legacy of "Midtown South" remains the foundation. Below, we have preserved our original neighborhood guide and directory.

Whether you’re here for the classic landmarks or the deep-cut history of this transition zone, the "Legacy Page" continues below to ensure no stone—or storefront—is left unturned:

Midtown South - Legacy Page

Geographic Setting

Bounded by West 30th Street to the south and West 34th Street to the north, and stretching from Ninth Avenue eastward to Madison Avenue, Midtown South occupies one of Manhattan’s most strategically vital crossroads—a district where transportation, commerce, and architecture converge. Framed by Penn Station and Madison Square Garden on its western flank, and by the grand corridors of Fifth and Madison Avenues to the east, the neighborhood serves as a connective tissue between Chelsea, Murray Hill, and the great Midtown core above.

The area’s built form reflects its hybrid identity: a dense grid of early 20th-century loft buildings and Art Deco towers rising beside glass-and-steel corporate headquarters and new mixed-use developments. The High Line’s northern terminus and the Hudson Yards district lie just west of Ninth Avenue, while Koreatown stretches north from 32nd Street east of Fifth. The hum of Seventh Avenue, the clang of trains beneath Penn Station, and the steady flow of commuters along 34th Street define the district’s ceaseless motion. Yet amid this bustle, the area also possesses moments of civic grace—Greeley and Herald Squares, St. Francis of Assisi Church on West 31st, and restored lofts that recall the neighborhood’s industrial heyday.

Etymology and Origins

“Midtown South” is a modern geographic designation, coined by city planners and developers in the late 20th century to describe the lower portion of Midtown’s commercial belt, distinct from the higher-rise corporate district to the north. Historically, however, this area was known as the Tenderloin in the late 19th century—an entertainment and vice district of hotels, saloons, and theaters that thrived in the shadow of the city’s northward expansion. The arrival of Pennsylvania Station (1910) and the Hotel Pennsylvania (1919) redefined its character, transforming the area from nightlife corridor to transportation and business hub.

The name “Midtown South” captures its position as both part of Midtown and a threshold to downtown—a place perpetually in motion, neither fully modernist nor wholly industrial, but balanced between the two.

The Neighborhood

19th Century: The Tenderloin and the Tracks

In the late 1800s, this section of Manhattan was one of the city’s liveliest and most notorious neighborhoods. Centered around Sixth and Seventh Avenues, the Tenderloin District housed theaters, gambling halls, and restaurants that catered to the upper classes by day and a racier clientele by night. Elegant brownstones coexisted uneasily with dance halls and stables, while the elevated railways along Sixth and Ninth Avenues thundered overhead.

At the same time, the area began to assume an industrial and transportation character. Freight yards and warehouses lined the West Side, while the New York Central Railroad and later Pennsylvania Railroad eyed the neighborhood for future expansion. By the 1890s, reformers decried the Tenderloin’s vice, and real estate interests saw opportunity in its clearance and redevelopment. The stage was set for monumental transformation in the new century.

Early 20th Century: The Age of Penn Station and Commerce

The arrival of Pennsylvania Station, opened in 1910 at Seventh Avenue and 33rd Street, was a watershed moment. Designed by McKim, Mead & White, the station’s vast colonnades and marble concourses epitomized Beaux-Arts grandeur and marked the beginning of Midtown South’s modern identity. The simultaneous excavation of the Hudson and East River Tunnels connected New Jersey and Long Island directly to Manhattan, cementing the area’s role as the city’s primary rail gateway.

In the surrounding blocks, new hotels and office buildings rose to serve travelers and businesses. The Hotel Pennsylvania (1919), across Seventh Avenue, became the largest hotel in the world, its telephone number—Pennsylvania 6-5000—immortalized in song. The Moynihan Train Hall’s predecessor, the Farley Post Office (1914), stretched majestically along Eighth Avenue, symbolizing the federal presence in the city’s infrastructural heart. Eastward, the Garment District, spreading along Seventh Avenue and Broadway, filled the air with the hum of sewing machines and delivery trucks.

Midtown South thus became both gateway and workshop—a district where travelers arrived, goods were made, and the machinery of commerce never ceased.

Mid-20th Century: Decline, Industry, and Transition

The mid-century brought both prosperity and peril. As the garment trade flourished through the 1930s–1950s, factories and showrooms dominated the upper floors of masonry loft buildings on Thirty-second, Thirty-third, and Thirty-fourth Streets. The street-level energy was frenetic: garment runners, delivery vans, and pushcarts turned every block into a scene of working-class vitality.

Yet postwar urban change soon eroded that fabric. The demolition of the original Penn Station in 1963 to make way for Madison Square Garden (opened 1968) and the subterranean Penn Station complex symbolized the shift from grandeur to utility. The surrounding blocks suffered neglect, their once-proud lofts turned to storage or disuse as the garment industry declined and suburbanization siphoned commerce outward. By the 1970s, Midtown South had become a shadow of its former self—its grandeur buried beneath grime and exhaust, its sidewalks crowded with commuters rather than couture.

Late 20th Century: Renewal through Reinvention

The 1980s and 1990s brought gradual reinvestment, as the city’s real estate cycle rediscovered the potential of Midtown South’s solid industrial architecture and unmatched transit access. The term “Midtown South” gained currency as developers converted old lofts into creative offices and technology hubs. New zoning encouraged mixed use, while proximity to Penn Station, Herald Square, and Madison Square Garden made the district attractive to media and design firms.

Koreatown, centered along East 32nd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, emerged during this period, infusing the neighborhood with new life—restaurants, grocery markets, karaoke bars, and cultural venues that transformed the streetscape after dark. Meanwhile, Greeley Square and Herald Square underwent redesign, gaining new plazas, trees, and lighting. By the late 1990s, Midtown South had regained vitality—not as a garment hub or vice district, but as a center of creative commerce.

21st Century: The Connected Core

In the 21st century, Midtown South has become one of the city’s most dynamic and adaptive neighborhoods. The western blocks, once dominated by industrial uses, have been reshaped by the Hudson Yards and Moynihan Train Hall projects, restoring grandeur to Penn Station’s long-maligned western face. To the east, new boutique hotels, coworking spaces, and tech offices fill restored prewar buildings whose high ceilings and robust construction perfectly suit 21st-century work culture.

The NoMad district (North of Madison Square Park) just south of 30th Street extends its influence northward, bringing high-end residential towers and Michelin-starred restaurants to the fringe of Midtown South. Yet amid change, traces of history remain: the limestone façades of the old Pennsylvania Station Post Office, the surviving Art Deco lettering on garment buildings, and the morning queues of commuters that have animated the district for over a century.

Today, the neighborhood stands at the nexus of transformation—its streets linking old industry to new innovation, its architecture bridging eras of utility and aspiration.

Spirit and Legacy

Midtown South’s legacy is motion—of trains, trades, and transformations. It is where America’s grandest rail station once stood and where millions still pass each day; where factories hummed and now studios and startups thrive. Its streets carry the accumulated weight of the city’s labor, yet its skyline embodies rebirth: each generation rebuilding atop the bones of the last.

New York City

Use this custom Google map to explore where every neighborhood in all five boroughs of New York City is located.

The Five Boroughs

One of New York City’s unique qualities is its organization in to 5 boroughs: Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, The Bronx, and Staten Island. These boroughs are part pragmatic administrative districts, and part vestiges of the region’s past. Each borough is an entire county in New York State - in fact, Brooklyn is, officially, Kings County, while Staten Island is, officially Richmond County. But that’s not the whole story …

Initially, New York City was located on the southern tip of Manhattan (now the Financial District) that was once the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. Across the East River, another city was rising: Brooklyn. In time, the city planners realized that unification between the rapidly rising cities would create commercial and industrial opportunities - through streamlined administration of the region.

So powerful was the pull of unification between New York and Brooklyn that three more counties were pulled into the unification: The Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island. And on January 1, 1898, the City of New York unified two cities and three counties into one Greater City of New York - containing the five boroughs we know today.

But because each borough developed differently and distinctly until unification, their neighborhoods likewise uniquely developed. Today, there are nearly 390 neighborhoods, each with their own histories, cultures, cuisines, and personalities - and each with residents who are fiercely proud of their corner of The Big Apple.