EAST VILLAGE

Manhattan

Geographic Setting

The East Village occupies one of Lower Manhattan’s most storied landscapes—a wedge of the old city bounded by Fourth Avenue to the west and Avenue A to the east, East 14th Street to the north, and a southern line that traces East 4th Street from Cooper Square to First Avenue, then dips south along First Avenue to Houston Street, enclosing the historic blocks between First Avenue and Avenue A. Within these bounds lies a neighborhood that has repeatedly redefined New York’s countercultural identity: a district where immigrant tenements, avant-garde theaters, punk clubs, and community gardens have coexisted for generations in unlikely harmony.

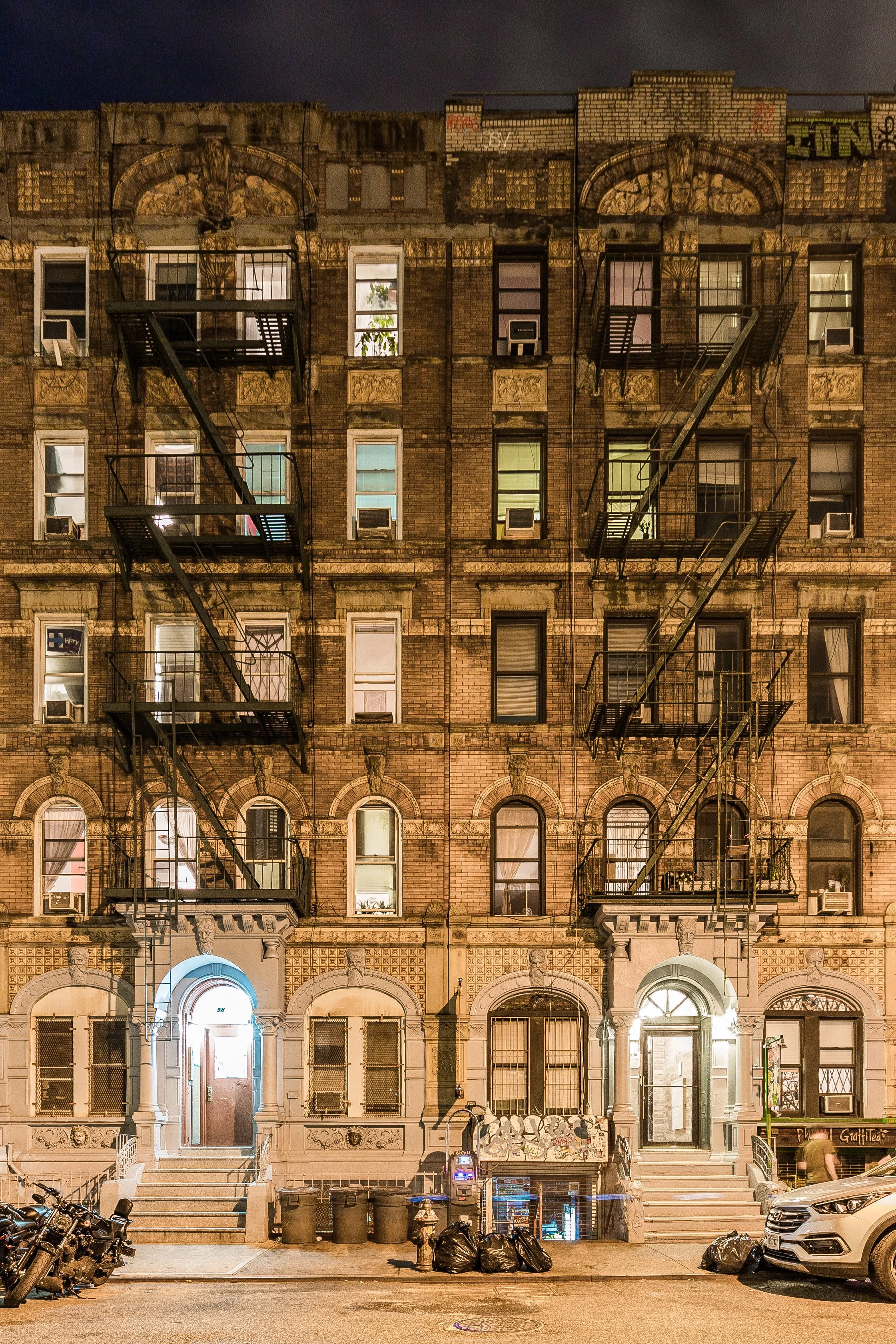

The topography is characteristically flat—reclaimed 18th-century marshland once fed by the Stuyvesant Meadows and the Minetta Brook—but the human landscape is anything but level. St. Mark’s Place, Tompkins Square Park, and the parallel corridors of East 7th through East 10th Streets form its emotional and architectural spine. Here, the grid narrows into intimate blocks lined with 19th-century tenements, fire escapes, cafés, and bookshops. Despite waves of redevelopment, the East Village retains the small-scale, human texture of Old New York—its history written in brick, iron, and graffiti.

Etymology and Origins

Though officially part of the Lower East Side through most of its history, the name “East Village” gained common use only in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when artists and writers fleeing the rising rents of Greenwich Village began settling east of Fourth Avenue. Real estate agents coined the new term to capture its bohemian appeal, but the neighborhood’s roots stretch far deeper.

This land once formed part of Peter Stuyvesant’s 17th-century farm, or “bouwerie”, from which nearby The Bowery takes its name. The Stuyvesant family’s country estate, centered near today’s St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, dominated the area well into the 18th century. As Manhattan expanded northward in the early 1800s, the estate was subdivided into residential lots. Rows of Federal and Greek Revival townhouses rose along St. Mark’s Place and Second Avenue, then one of the city’s grandest residential boulevards—lined with theaters, concert halls, and synagogues. By mid-century, however, the wealthy had moved uptown, and the East Village—like much of the Lower East Side—became home to waves of immigrants seeking foothold and community.

The Neighborhood

19th Century: Immigration, Industry, and Faith

In the 1840s–1880s, the East Village became one of New York’s great immigrant frontiers. German immigrants, escaping revolution and economic hardship, filled the district east of Second Avenue, transforming it into “Kleindeutschland” (Little Germany)—the largest German-speaking community in the United States. Beer gardens, shooting clubs, and social halls filled the avenues; Tompkins Square Park, opened in 1834, became the neighborhood’s central gathering place for festivals, parades, and occasionally protests.

Religious and educational institutions flourished: St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery (1799), one of Manhattan’s oldest churches, remained an anchor of civic life; St. Nicholas Kirche and numerous German schools served the immigrant population. Yet the prosperity of Little Germany was shattered in 1904, when the General Slocum steamboat disaster on the East River claimed more than a thousand lives, nearly all from the community. The tragedy precipitated an exodus uptown to Yorkville, leaving behind a vacancy soon filled by Eastern European Jews, Poles, Ukrainians, and Russians.

By the turn of the century, the East Village had become a dense, multilingual patchwork of tenements and synagogues. The grand theaters along Second Avenue evolved into the Yiddish Theater District, known as “the Jewish Rialto,” where stars like Jacob Adler and Molly Picon drew crowds. The neighborhood pulsed with cultural life even amid poverty—a microcosm of New York’s immigrant city in full stride.

Early–Mid 20th Century: Political Radicalism and Cultural Crossroads

The early 20th century saw the East Village emerge as a center of radical thought and working-class activism. Anarchist and socialist newspapers thrived; political meetings filled Tompkins Square. Immigrant laborers joined garment and dockworker unions that shaped the broader labor movement. In these same streets, tenement reformers like Lillian Wald and organizations like the Henry Street Settlement pioneered social work that transformed urban welfare.

By the 1930s–40s, the area’s population shifted again. Jewish and Italian families mixed with Ukrainians and Poles fleeing war and upheaval in Europe. Along Second Avenue, Ukrainian churches and community halls replaced old German saloons, anchoring the neighborhood as the heart of Ukrainian-American life in New York. Meanwhile, experimental artists and students drawn by cheap rents began arriving in the postwar years, laying the groundwork for the East Village’s next incarnation.

East Village Photographic Video

1960s–1980s: Counterculture, Punk, and Urban Struggle

The 1960s marked the East Village’s transformation into the crucible of American counterculture. The Beat poets, having migrated from the West Village, found sanctuary in its cheap apartments and smoky coffeehouses. Allen Ginsberg lived and wrote here; Abbie Hoffman staged political theater on its streets. St. Mark’s Place became a legendary corridor of art, music, and rebellion. The Fillmore East, opened in 1968 in a former Yiddish theater, hosted performances by Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and The Grateful Dead, transforming Second Avenue into a pilgrimage site of rock history.

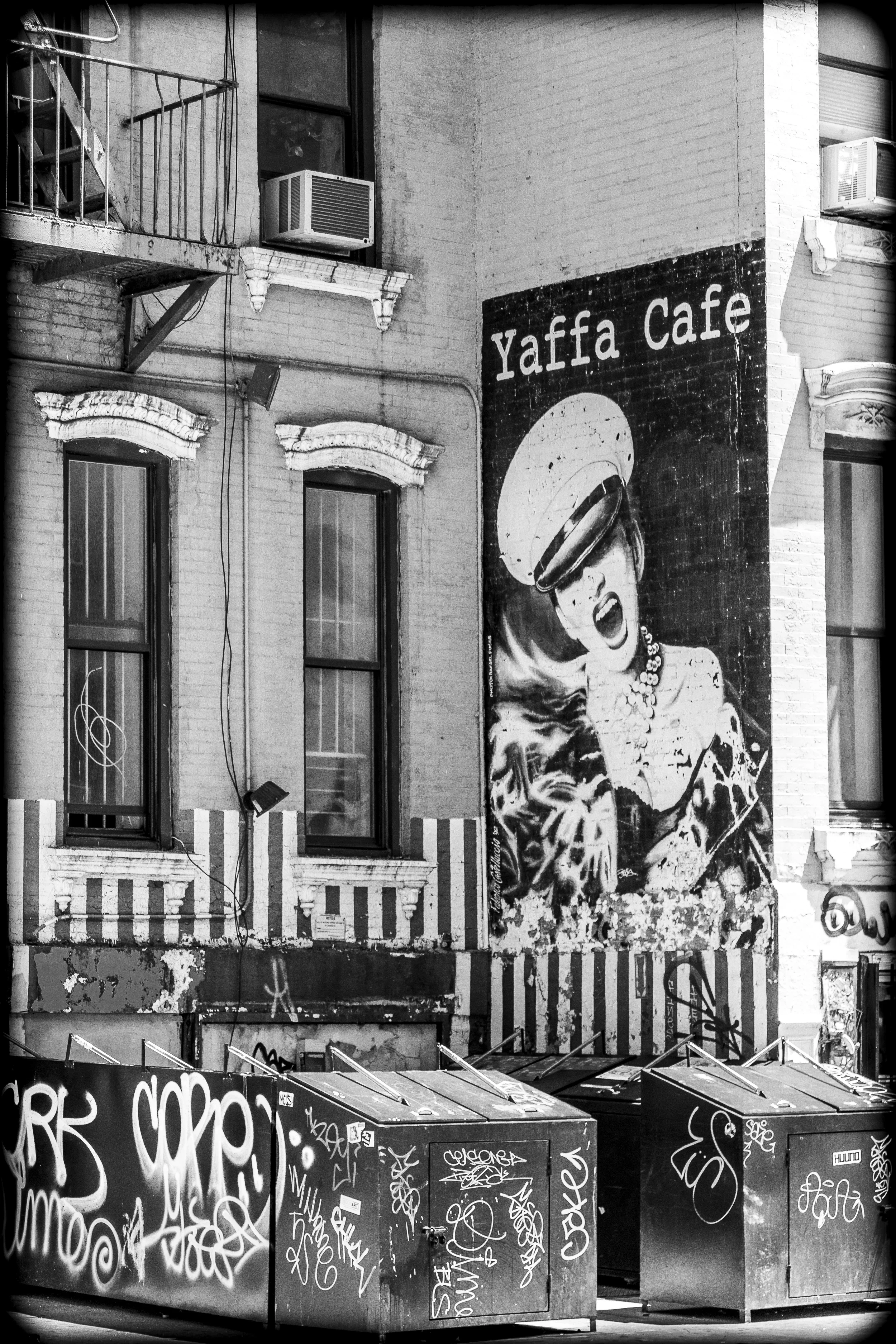

By the late 1970s, amid disinvestment and abandonment, the East Village became both a symbol of decay and an engine of creativity. Punk erupted at CBGB on the Bowery, giving voice to the city’s disaffected youth through bands like The Ramones, Patti Smith, and Talking Heads. Empty lots became community gardens; squats turned into art collectives. Tompkins Square Park served alternately as stage and battleground—site of concerts, protests, and the infamous 1988 Tompkins Square Riot, which crystallized tensions over housing, policing, and gentrification.

Despite hardship, the neighborhood’s independent spirit never dimmed. The East Village’s clubs, zines, and performance spaces—La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, PS122, and Nuyorican Poets Café—defined New York’s avant-garde for decades, blending activism, art, and identity.

21st Century: Memory, Change, and Persistence

Today, the East Village stands at the crossroads of preservation and transformation. Rising rents and new developments have replaced many of the old tenements and music venues, yet the neighborhood’s layered history remains visible in its architecture and institutions. The Ukrainian diners and Orthodox churches along Second Avenue, the Japanese restaurants on East 9th Street, and the independent bookstores and tattoo parlors on St. Mark’s Place all coexist within a few square blocks.

The East Village/Lower East Side Historic District, designated in 2012, protects many of its 19th-century buildings, while community groups continue to safeguard its gardens and parks as vital green lungs in the urban fabric. The echoes of its countercultural past remain palpable: murals honor Ginsberg and Joe Strummer, and Tompkins Square still hosts music festivals and rallies that keep its activist soul alive.

New residents have brought affluence and amenity, but the East Village’s defining characteristic endures—its capacity to reinvent itself without erasing its past, to remain both sanctuary and experiment in the city’s restless evolution.

East Village Photo Gallery

Spirit and Legacy

The East Village’s legacy is rebellion as heritage. From Stuyvesant’s farmland to immigrant tenements, from anarchist presses to punk stages, it has been a proving ground for every idea too radical, too experimental, or too alive to begin elsewhere. Its streets bear the layers of a city forever remaking itself: the chants of protest mingling with the strains of jazz, the scent of incense and pizza drifting together under neon and brick.

New York City

Use this custom Google map to explore where every neighborhood in all five boroughs of New York City is located.

The Five Boroughs

One of New York City’s unique qualities is its organization in to 5 boroughs: Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, The Bronx, and Staten Island. These boroughs are part pragmatic administrative districts, and part vestiges of the region’s past. Each borough is an entire county in New York State - in fact, Brooklyn is, officially, Kings County, while Staten Island is, officially Richmond County. But that’s not the whole story …

Initially, New York City was located on the southern tip of Manhattan (now the Financial District) that was once the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. Across the East River, another city was rising: Brooklyn. In time, the city planners realized that unification between the rapidly rising cities would create commercial and industrial opportunities - through streamlined administration of the region.

So powerful was the pull of unification between New York and Brooklyn that three more counties were pulled into the unification: The Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island. And on January 1, 1898, the City of New York unified two cities and three counties into one Greater City of New York - containing the five boroughs we know today.

But because each borough developed differently and distinctly until unification, their neighborhoods likewise uniquely developed. Today, there are nearly 390 neighborhoods, each with their own histories, cultures, cuisines, and personalities - and each with residents who are fiercely proud of their corner of The Big Apple.