MEATPACKING DISTRICT

Manhattan

Geographic Setting

Stretching from Gansevoort Street north to 14th Street, and from the Hudson River east to roughly Hudson Street, the Meatpacking District occupies one of the most distinct and atmospheric corners of Lower Manhattan. Once a gritty warren of cobblestone streets and refrigerated warehouses, it has become a celebrated fusion of past and present — a neighborhood where 19th-century industrial architecture frames the glassy façades of contemporary design. Bordered by the West Village, Chelsea, and the Hudson River Park, this compact district hums with creative energy, nightlife, and memory — an urban palimpsest where the scent of salt, iron, and perfume still lingers in the air.

Etymology and Origins

The name Meatpacking District stems directly from its historic role as one of New York’s central meat distribution hubs. By the early 1900s, more than 250 slaughterhouses, packing plants, and refrigeration facilities operated within a few square blocks, supplying meat to restaurants, grocers, and markets throughout the city. Its industrial identity, however, grew from much older roots.

In the colonial era, this area lay within the Greenwich Village Common Lands, a stretch of tidal marshes and small farms along the river. The 18th-century Gansevoort Market, named for General Peter Gansevoort, a Revolutionary War hero and grandfather of novelist Herman Melville, became the district’s nucleus when it was formally established in 1884. The nearby Hudson River piers and elevated freight lines gave it direct access to ships, trains, and warehouses — the lifelines of a growing metropolis.

The Neighborhood

19th Century: From Farmland to Freight Yards

In the early 19th century, the neighborhood was a semi-rural outpost on Manhattan’s western edge, known for its open-air markets and small-scale industry. By the 1840s, as the city’s population exploded, the area transformed into a nexus of food distribution and manufacturing. Butchers, tanners, and grocers filled the cobblestoned streets around Washington and Little West 12th Streets, their work supported by the nearby waterfront’s wharves and rail sidings.

The construction of the Hudson River Railroad Freight Yard and later the High Line, completed in 1934, solidified the district’s industrial dominance. The elevated tracks ran directly through warehouses and cold-storage buildings, allowing trains to deliver goods — including meat — straight into upper-level loading docks. The smell of ice, sawdust, and iron defined the daily rhythm.

Early 20th Century: The Reign of Industry

By the turn of the century, the Meatpacking District was an industrial powerhouse. Its grid of low-slung brick buildings, iron shutters, and cobblestone lanes reflected an economy built on precision and repetition. Men in white aprons worked through the night; the hum of refrigeration compressors mingled with the whistle of tugboats on the river.

Yet within its utilitarian landscape, a distinctive community emerged — one bound by labor, toughness, and camaraderie. Family-owned companies operated for generations; neighborhood taverns and diners catered to night-shift workers. Though physically close to the elegance of Greenwich Village, it was socially worlds apart: blue-collar, unadorned, and vital.

The area also absorbed other trades — produce, poultry, and manufacturing — which operated alongside the meatpackers in uneasy harmony. Floodlights illuminated the streets before dawn as deliveries poured in, giving the district an unending rhythm of work that would last into the 1970s.

Mid-20th Century: Decline and Subculture

The district’s fortunes began to wane in the postwar decades. Refrigerated trucking, container shipping, and suburban distribution centers rendered the city’s meat markets obsolete. Many companies closed or moved to the Bronx’s Hunts Point Cooperative Market, established in 1967. By the 1980s, only a handful of meatpackers remained, their loading docks surrounded by shuttered warehouses and vacant lots.

Yet even in decline, the neighborhood found new life at the margins. The empty streets and low rents drew artists, nightclubs, and outsiders. During the 1970s and 1980s, the Meatpacking District became one of the city’s most significant LGBTQ+ spaces — raw, dangerous, and liberating. The Anvil, Hellfire Club, and later The Mineshaft operated here, underground venues that became symbols of sexual freedom and queer resistance during an era of repression and the emerging AIDS crisis.

Photographers and filmmakers were drawn to the area’s visual power — its desolate beauty, decaying infrastructure, and chiaroscuro of light and shadow. It became both stage and metaphor: the city’s industrial carcass reanimated by subculture and survival.

Meatpacking District Photographic Tour

Late 20th Century: The Dawn of Reinvention

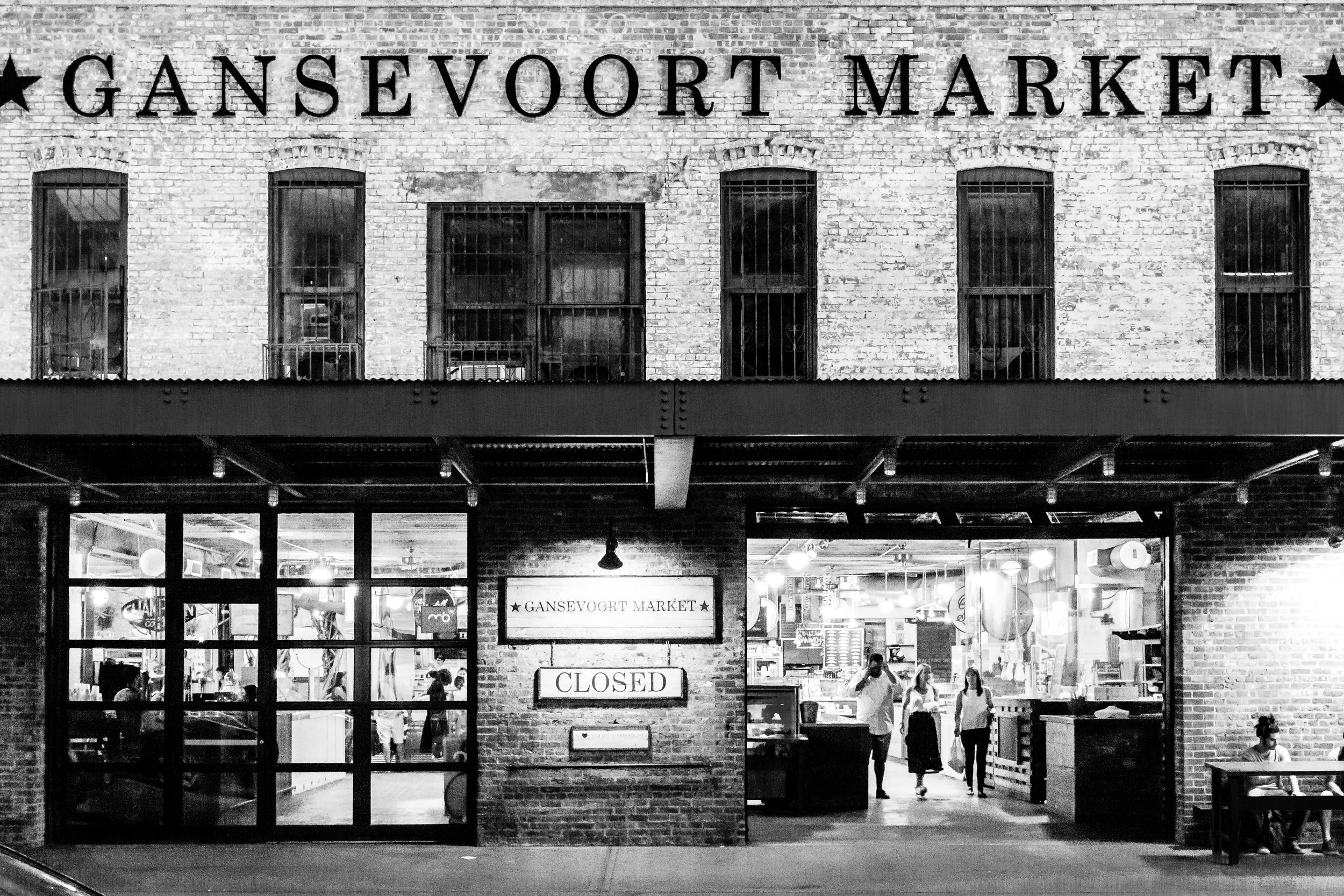

By the 1990s, the Meatpacking District had entered its next transformation. Artists and entrepreneurs saw opportunity in the weathered brick buildings and cobblestoned streets. Boutique designers, galleries, and restaurants began moving in, repurposing loading docks as storefronts and studios. The Gansevoort Market Historic District was officially designated in 2003, protecting nearly 11 blocks of late-19th- and early-20th-century industrial architecture — a victory for preservationists who recognized the neighborhood’s rare authenticity.

The pivotal catalyst came with the High Line’s rebirth. Once an abandoned railway, it was reimagined as an elevated park in the early 2000s. The first section opened in 2009, transforming the district’s skyline into a suspended garden of wild grasses, art installations, and panoramic vistas. The High Line’s success brought a global spotlight to the neighborhood and spurred a wave of redevelopment along its path.

21st Century: Design, Culture, and Commerce

In the 21st century, the Meatpacking District stands at the confluence of history and design. Historic warehouses have been adapted into sleek spaces for fashion houses, tech firms, and cultural institutions. The Whitney Museum of American Art, designed by Renzo Piano and opened in 2015 at the southern terminus of the High Line, anchors the district’s cultural identity. Its terraces overlook the river, the park, and the very cobblestones that once ran with ice and sawdust.

Nearby, the Google Chelsea campus occupies former Nabisco and industrial buildings, signaling the area’s shift from manual labor to digital enterprise. Yet despite luxury storefronts and gleaming hotels, vestiges of the old district persist: a few working meat distributors on Gansevoort and Little West 12th Streets, their delivery trucks parked beside high-end boutiques at dawn.

Public plazas, such as Gansevoort Plaza, and preserved cobblestones lend the neighborhood its cinematic quality. The tension between preservation and progress — between the scent of espresso and that of raw meat — defines its atmosphere.

Meatpacking District Photo Gallery

Architecture and Atmosphere

Architecturally, the Meatpacking District is a dialogue between permanence and adaptation. Its signature low-rise brick warehouses, with iron canopies and loading docks, speak of the industrial age, while glass additions and adaptive reuse projects express contemporary urbanism’s flexibility. The cobblestones, laid in the 1800s, glisten in the rain beneath the reflected light of modern façades — a literal meeting of centuries.

The atmosphere is electric yet oddly grounded. By day, designers, tourists, and workers share the streets; by night, the area pulses with nightlife and art. The mix of textures — brick, glass, steel, and stone — mirrors the mix of people: old-timers who remember the market’s heyday and newcomers who see only its creative glamour.

Spirit and Legacy

The legacy of the Meatpacking District is transformation through authenticity. Few neighborhoods have reinvented themselves so completely while preserving their physical memory. From slaughterhouses to fashion runways, from freight lines to elevated gardens, it remains a testament to New York’s cyclical genius for reinvention — always building on its own bones.

New York City

Use this custom Google map to explore where every neighborhood in all five boroughs of New York City is located.

The Five Boroughs

One of New York City’s unique qualities is its organization in to 5 boroughs: Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, The Bronx, and Staten Island. These boroughs are part pragmatic administrative districts, and part vestiges of the region’s past. Each borough is an entire county in New York State - in fact, Brooklyn is, officially, Kings County, while Staten Island is, officially Richmond County. But that’s not the whole story …

Initially, New York City was located on the southern tip of Manhattan (now the Financial District) that was once the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. Across the East River, another city was rising: Brooklyn. In time, the city planners realized that unification between the rapidly rising cities would create commercial and industrial opportunities - through streamlined administration of the region.

So powerful was the pull of unification between New York and Brooklyn that three more counties were pulled into the unification: The Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island. And on January 1, 1898, the City of New York unified two cities and three counties into one Greater City of New York - containing the five boroughs we know today.

But because each borough developed differently and distinctly until unification, their neighborhoods likewise uniquely developed. Today, there are nearly 390 neighborhoods, each with their own histories, cultures, cuisines, and personalities - and each with residents who are fiercely proud of their corner of The Big Apple.