MURRAY HILL

Manhattan

Geographic Setting

Bounded by East 34th Street to the south and East 40th Street to the north (extending to East 42nd Street east of Third Avenue), Fifth Avenue to the west, and the East River to the east—with Tudor City excluded—Murray Hill occupies one of Midtown’s most historic and graceful residential enclaves. Lying just east of the commercial canyons of Fifth Avenue and west of the East River’s modern skyline, the neighborhood bridges the worlds of old brownstone Manhattan and the modern Midtown core.

Its streets—particularly East 36th through 38th—are lined with preserved 19th-century rowhouses shaded by elms and maples, giving the district a residential intimacy rarely found so close to Grand Central’s bustle. Park Avenue and Madison Avenue frame its western boundary with stately apartment houses and small hotels, while Lexington and Third Avenues pulse with restaurants, cafés, and markets serving a cosmopolitan mix of residents and professionals. East of Second Avenue, the terrain slopes gently toward the river, where St. Vartan Park, the East River Greenway, and the United Nations complex beyond Tudor City create a horizon of open sky and water. Murray Hill’s enduring identity is that of a neighborhood in equilibrium—urban but genteel, modern yet anchored in deep historical roots.

Etymology and Origins

The neighborhood takes its name from the Murray family, Quaker merchants who owned much of this land in the 18th century. Robert Murray and his wife, Mary Lindley Murray, established their country estate, Inclenberg (“Beautiful Hill”), on a rise between present-day Park Avenue and Lexington Avenue around East 36th Street. During the Revolutionary War, in September 1776, as British troops advanced northward after landing at Kips Bay, Mary Murray famously invited British officers to tea at her mansion—delaying them long enough for General George Washington’s troops to retreat north to safety. This act of grace and patriotism became one of New York’s most cherished Revolutionary anecdotes, and the Murray name has been synonymous with quiet courage and refinement ever since.

Following the war, the estate’s hilltop remained rural well into the 19th century, its orchards and meadows bounded by stone walls and paths leading toward the East River ferry landings. The eventual leveling of the hill for the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 erased Inclenberg’s topography but preserved its memory in the name “Murray Hill.”

The Neighborhood

18th–19th Centuries: From Country Estate to City Grid

For decades after the Revolution, Murray Hill remained semi-rural, its fields and orchards stretching down toward the East River. The Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, which imposed the city’s rigid grid upon the landscape, divided the Murray estate into rectangular lots. Urbanization followed slowly: by the 1830s, a handful of Greek Revival and Italianate rowhouses began to appear along the new streets, their stoops shaded by young trees.

The arrival of the New York and Harlem Railroad along Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue) in 1837 connected the area to downtown, accelerating development. By mid-century, Murray Hill had become a favored residential district for New York’s mercantile and professional elite. Its location — elevated, quiet, and equidistant from the commercial core and the East River — offered both prestige and privacy.

Late 19th Century: A Genteel Neighborhood of Brownstones

By the late 1800s, Murray Hill was one of the city’s most fashionable residential quarters. Stately brownstone and limestone townhouses lined East 36th through 39th Streets, often adorned with carved lintels, bay windows, and iron railings. The neighborhood attracted prominent families and dignitaries, including financier J. P. Morgan, whose red sandstone mansion at Madison Avenue and 36th Street became the nucleus of today’s Morgan Library & Museum.

The construction of Grand Central Terminal (opened 1913) just to the north further solidified the district’s prominence. Though nearby Midtown began to sprout skyscrapers, Murray Hill retained its low-rise grace, shielded by restrictive covenants and civic advocacy. Churches such as The Church of the Incarnation (1864) and institutions like the Union League Club anchored the area’s social fabric, while the Murray Hill Hotel (1884) became a symbol of its genteel hospitality.

Early 20th Century: Transition and Adaptation

As the 20th century dawned, Murray Hill’s quiet lanes stood in contrast to the frenetic growth around them. While neighboring Fifth Avenue surrendered its mansions to department stores and office towers, Murray Hill’s brownstones largely survived, gradually adapted for new uses. Many became boardinghouses, consulates, or medical offices, preserving their façades even as interiors changed.

The neighborhood’s proximity to the New York Public Library, Grand Central, and the burgeoning Midtown business district attracted professionals who valued both convenience and dignity. Apartment houses such as the Deauville, the Murray Hill Crescent, and the Windsor Tower (in nearby Tudor City) offered modern living without sacrificing refinement.

The early decades of the century also brought an influx of immigrants, particularly from Ireland and Eastern Europe, who found employment in domestic service or the nearby garment trade. Their presence added vitality to the area’s social landscape.

Murray Hill Photographic Tour

Mid-20th Century: Preservation amid Progress

After World War II, Murray Hill faced the pressures of modernization that transformed much of Manhattan. Office towers and hotels began to encroach from the west, and the elevated trains along Park Avenue were replaced by a sunken rail line covered with landscaped medians. The result was paradoxical: increased accessibility yet preserved calm.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Murray Hill became a favored address for United Nations diplomats, whose missions and residences clustered near Second Avenue. Embassies from countries such as Mexico, Poland, and South Africa occupied former brownstones, giving the neighborhood an international character. Despite the city’s rapid verticalization, local advocacy ensured that much of Murray Hill’s residential core retained its 19th-century charm.

The Murray Hill Neighborhood Association, founded in 1958, successfully campaigned for preservation zoning and the protection of architectural landmarks. Their efforts culminated in the 1989 designation of the Murray Hill Historic District, securing more than 60 buildings as part of the city’s protected heritage.

Late 20th Century: A Stable Enclave in a Changing City

Through the 1970s and 1980s, Murray Hill maintained its identity as a stable, middle- to upper-middle-class enclave amid the city’s turbulence. Many of its brownstones were restored by new homeowners and professionals drawn to the area’s central location and human scale. Small businesses — delis, florists, antique shops — flourished along Lexington and Third Avenues, while the side streets remained remarkably tranquil.

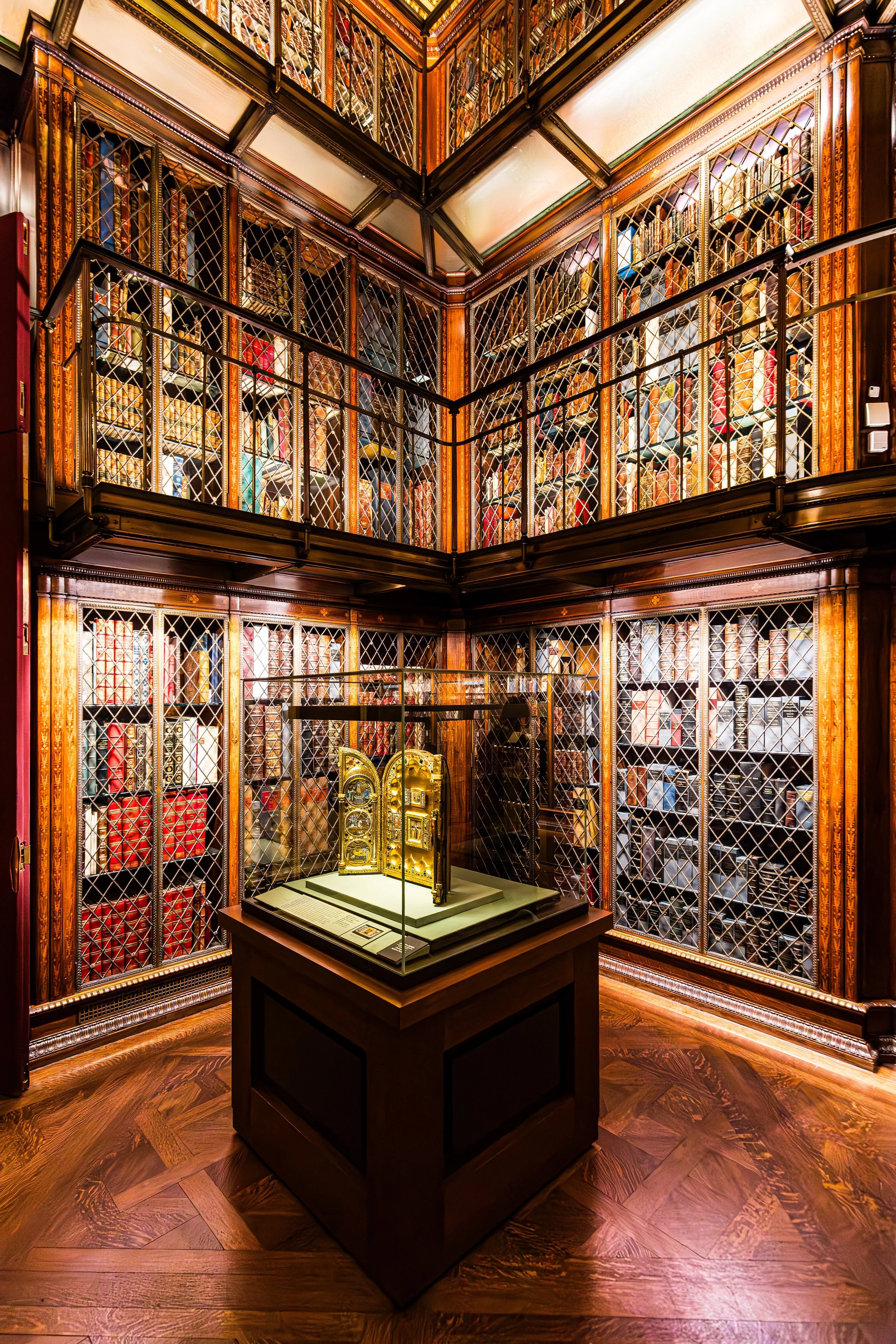

The presence of the Morgan Library & Museum, which underwent major expansions in 1928 and 2006, reinforced the neighborhood’s cultural stature. Housing a priceless collection of manuscripts, rare books, and art, the Morgan stands as Murray Hill’s intellectual beacon — an institution that embodies the neighborhood’s blend of refinement and accessibility.

21st Century: Quiet Renewal and Enduring Character

Today, Murray Hill balances heritage with modernity. Its streetscape remains among the most intact 19th-century environments in Midtown Manhattan, yet its population is as dynamic as the city itself — a mix of long-term residents, young professionals, and international diplomats. New condominium towers have appeared along the avenues, but zoning regulations continue to preserve the intimate scale of the side streets.

The East River Greenway, St. Vartan Park, and proximity to both Midtown East and Kips Bay add to its livability. Tree-lined blocks between Park and Lexington retain their brownstone rhythm, their stoops adorned with seasonal flowers and flags. From many corners, one can still glimpse the gleaming spire of the Chrysler Building, a reminder that Murray Hill remains poised between the old and the new — between the domestic and the monumental.

Murray Hill Photo Gallery

Architecture and Atmosphere

Architecturally, Murray Hill is a microcosm of New York’s stylistic evolution. Greek Revival rowhouses stand beside Romanesque brownstones and early 20th-century apartment houses. Limestone façades, leaded-glass transoms, and wrought-iron fences lend a tactile richness. The Morgan Library’s Renaissance-inspired façade by Charles McKim provides a focal point of artistic gravity, while the nearby consulates and townhouses maintain a genteel urbanity rare in the city’s core.

The atmosphere is one of hushed vitality. Mornings bring the sound of church bells and the scent of fresh coffee from corner cafés; evenings find quiet conversation on stoops or soft light spilling from townhouse windows. It is a neighborhood that feels self-contained — urban yet intimate, worldly yet personal.

Spirit and Legacy

Murray Hill’s legacy is refinement through continuity — a neighborhood that has adapted to modernity without losing its soul. From Mary Murray’s fabled Revolutionary tea table to the hushed halls of the Morgan Library, from 19th-century rowhouses to 21st-century apartments, it embodies the quiet confidence of a city that honors its past while embracing its future.

New York City

Use this custom Google map to explore where every neighborhood in all five boroughs of New York City is located.

The Five Boroughs

One of New York City’s unique qualities is its organization in to 5 boroughs: Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, The Bronx, and Staten Island. These boroughs are part pragmatic administrative districts, and part vestiges of the region’s past. Each borough is an entire county in New York State - in fact, Brooklyn is, officially, Kings County, while Staten Island is, officially Richmond County. But that’s not the whole story …

Initially, New York City was located on the southern tip of Manhattan (now the Financial District) that was once the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. Across the East River, another city was rising: Brooklyn. In time, the city planners realized that unification between the rapidly rising cities would create commercial and industrial opportunities - through streamlined administration of the region.

So powerful was the pull of unification between New York and Brooklyn that three more counties were pulled into the unification: The Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island. And on January 1, 1898, the City of New York unified two cities and three counties into one Greater City of New York - containing the five boroughs we know today.

But because each borough developed differently and distinctly until unification, their neighborhoods likewise uniquely developed. Today, there are nearly 390 neighborhoods, each with their own histories, cultures, cuisines, and personalities - and each with residents who are fiercely proud of their corner of The Big Apple.