MORNINGSIDE HEIGHTS

Manhattan

Geographic Setting

Perched on a commanding plateau between 110th and 122nd Streets, bounded by Morningside Park to the east and Riverside Park to the west, Morningside Heights rises like an urban acropolis above the heart of Upper Manhattan. Known as “the Academic Acropolis,” the neighborhood hosts a remarkable concentration of cultural and intellectual institutions — among them Columbia University, Barnard College, Teachers College, the Union Theological Seminary, and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Framed by two great parks and overlooking the Hudson River, it is a neighborhood where learning, faith, and civic purpose converge — a place of ideas, ideals, and architectural grandeur.

Etymology and Origins

The name Morningside Heights was formalized in the 1890s when city planners sought to distinguish this elevated district west of Harlem and north of the Upper West Side. “Morningside” referred to the eastern park’s orientation toward the rising sun, while “Heights” described the high ground of Manhattan’s ancient schist ridge. Before urbanization, the area was rural and sparsely settled — known as part of the Bloomingdale District, a landscape of farms, country estates, and rocky bluffs.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, this ridge served as a strategic vantage point. During the Revolutionary War, the Battle of Harlem Heights (1776) unfolded across the surrounding hills, and remnants of fortifications were visible for decades afterward. The land’s commanding views and natural elevation later made it a prime location for institutions seeking both seclusion and symbolic stature.

The Neighborhood

19th Century: From Asylum to Academia

The first major development on the plateau was the relocation of the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum in 1821 from downtown Manhattan to what is now Columbia University’s campus. The asylum’s expansive, park-like grounds introduced the concept of therapeutic landscape architecture — a precursor to the institutional planning that would define Morningside Heights.

By the late 19th century, the asylum had moved north to White Plains, and the plateau lay largely undeveloped. It was then that a new vision took shape: the creation of an academic and religious enclave — a kind of American Athens on the Hudson. The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, whose cornerstone was laid in 1892, anchored this vision both spiritually and visually. Its colossal Gothic Revival design by George Lewis Heins and Christopher Grant LaFarge symbolized New York’s ambition to create a cathedral on par with Europe’s great monuments.

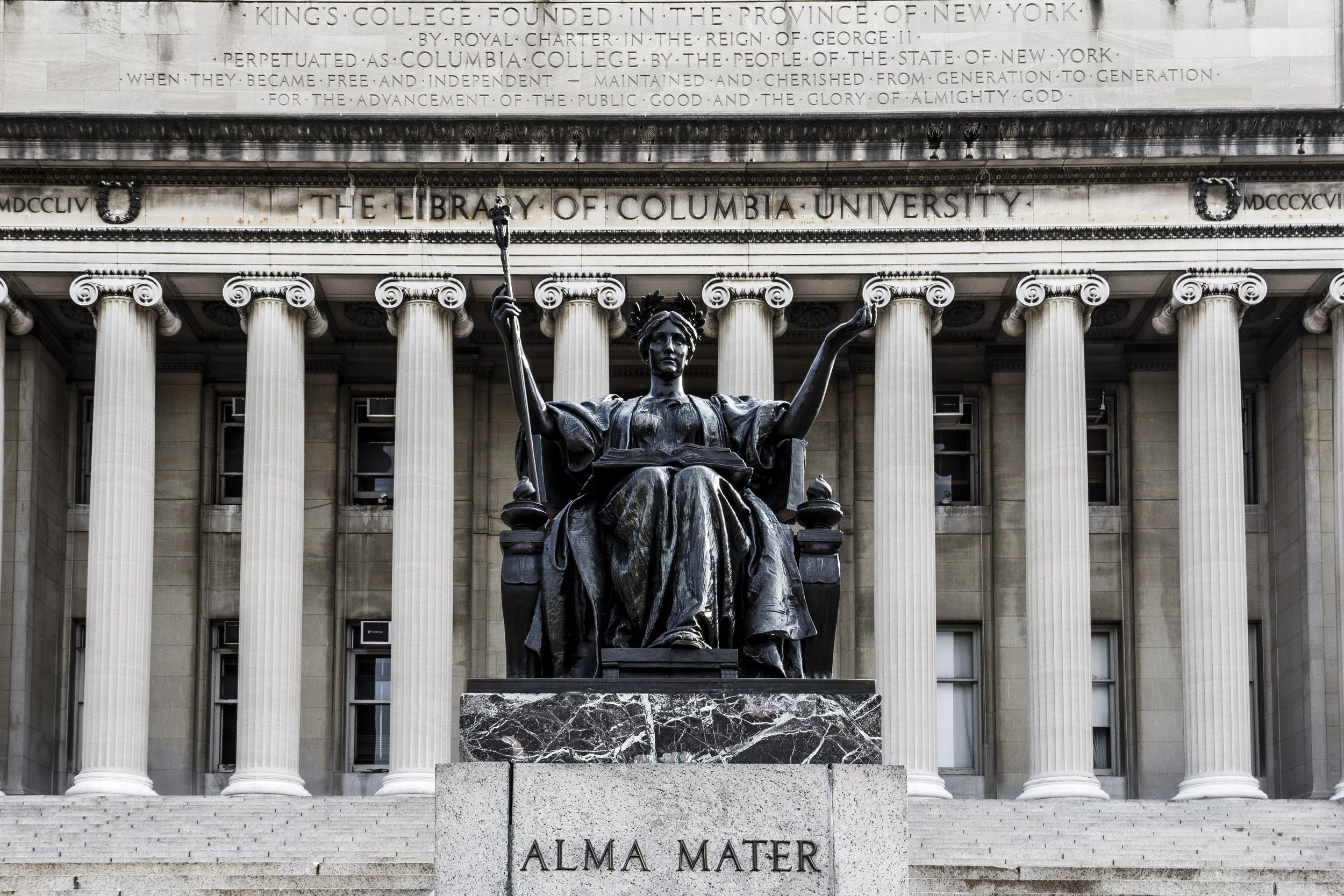

The arrival of Columbia University soon after completed the transformation. Having outgrown its midtown campus, Columbia moved here in 1897, commissioning the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White to design a unified campus in the neoclassical style. The resulting ensemble — Low Memorial Library, Butler Library, and their surrounding quadrangles — established a monumental order that set the tone for the neighborhood.

Early 20th Century: The Academic Acropolis

By the early 1900s, Morningside Heights had matured into the city’s intellectual and spiritual capital. In addition to Columbia and Barnard, Teachers College (founded 1887), the Union Theological Seminary (1910), and the Jewish Theological Seminary (1915) established campuses here, forming a cluster of institutions unmatched in density or influence. Together they shaped the education of countless leaders, artists, and thinkers who would define the 20th century.

Residential life flourished alongside academia. Elegant apartment houses rose along Riverside Drive and Claremont Avenue, designed for professors, clergy, and middle-class professionals. The Morningside Gardens cooperative complex, completed in the 1950s, would later embody the area’s commitment to progressive urban planning.

The neighborhood’s social landscape reflected the idealism of its institutions. Progressive movements, ecumenical dialogues, and social reform projects thrived here. Figures such as Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich at Union Seminary, and later W. E. B. Du Bois and Langston Hughes in nearby Harlem, made the area a crucible of intellectual and moral debate.

Mid-20th Century: Turbulence and Transition

The mid-20th century brought both prestige and challenge. After World War II, Columbia University expanded aggressively, acquiring new property and housing, sometimes at the expense of surrounding communities. The tensions between “town and gown” culminated in the student protests of 1968, when demonstrations against the Vietnam War and Columbia’s proposed gymnasium in Morningside Park brought national attention. The protests, which occupied campus buildings and drew thousands into the streets, symbolized the generational and social divides of the era.

Despite these upheavals, the neighborhood’s institutions endured and evolved. The 1970s saw Morningside Heights weathering the city’s fiscal crisis with resilience. Community organizations, churches, and cooperatives worked to stabilize housing and maintain safety. The neighborhood’s architectural cohesion and its powerful institutional anchors helped it avoid the severe decline experienced elsewhere in the city.

Morningside Heights Photographic Tour

Late 20th Century: Renewal and Preservation

By the 1980s and 1990s, Morningside Heights entered a period of renewal. Columbia University restored its historic campus buildings and expanded research facilities, while neighborhood residents advocated for preservation and equitable development. The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, though still unfinished, continued its dual role as house of worship and cultural venue, hosting concerts, art installations, and community events that linked sacred space to civic life.

At the same time, Riverside and Morningside Parks — both designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux — underwent significant restoration, reestablishing the green frame that defines the neighborhood’s character. The refurbished parks, with their stone staircases, promenades, and Hudson River views, offered both serenity and continuity to an area long associated with contemplation and renewal.

21st Century: Continuity and Modern Expansion

In the 21st century, Morningside Heights remains one of Manhattan’s most distinctive enclaves — at once intellectual, residential, and profoundly human in scale. Columbia’s new buildings, including the Jerome L. Greene Science Center and the Lenfest Center for the Arts just north in Manhattanville, have expanded the university’s footprint while linking the two neighborhoods more closely.

Residentially, Morningside Heights maintains a diverse population — faculty and students living alongside long-term residents, retirees, and young families. Cafés, bookstores, and corner delis lend the area a small-town warmth within the city’s vastness. The Cathedral Parkway (110th Street) subway station remains a symbolic gateway, connecting daily life to the city beyond while preserving the sense of elevation that defines the Heights.

Morningside Heights Photo Gallery

Architecture and Atmosphere

Architecturally, Morningside Heights is a masterpiece of civic design. The neoclassical symmetry of Columbia’s campus, the Gothic verticality of St. John the Divine, and the quiet dignity of prewar apartment houses together create a harmonious urban composition. Stone and brick dominate, softened by the greenery of the parks and courtyards. The neighborhood’s vistas — the Hudson at sunset, the cathedral spire rising through fog, the colonnades of Low Library glowing under lamplight — evoke both majesty and calm.

The atmosphere is contemplative yet alive. Bells toll from multiple chapels; students debate on campus steps; the hum of Riverside Drive mingles with birdsong from the parks. It is a neighborhood defined by rhythm rather than rush — a place that feels at once eternal and evolving.

Spirit and Legacy

Morningside Heights’ legacy is enlightenment made physical. It is a neighborhood built on the idea that learning, faith, and community are not separate pursuits but facets of the same human striving. Its institutions, architecture, and landscape together express a belief in progress guided by reflection — a balance rare in any city, and perhaps nowhere more eloquently realized than here.

New York City

Use this custom Google map to explore where every neighborhood in all five boroughs of New York City is located.

The Five Boroughs

One of New York City’s unique qualities is its organization in to 5 boroughs: Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, The Bronx, and Staten Island. These boroughs are part pragmatic administrative districts, and part vestiges of the region’s past. Each borough is an entire county in New York State - in fact, Brooklyn is, officially, Kings County, while Staten Island is, officially Richmond County. But that’s not the whole story …

Initially, New York City was located on the southern tip of Manhattan (now the Financial District) that was once the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. Across the East River, another city was rising: Brooklyn. In time, the city planners realized that unification between the rapidly rising cities would create commercial and industrial opportunities - through streamlined administration of the region.

So powerful was the pull of unification between New York and Brooklyn that three more counties were pulled into the unification: The Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island. And on January 1, 1898, the City of New York unified two cities and three counties into one Greater City of New York - containing the five boroughs we know today.

But because each borough developed differently and distinctly until unification, their neighborhoods likewise uniquely developed. Today, there are nearly 390 neighborhoods, each with their own histories, cultures, cuisines, and personalities - and each with residents who are fiercely proud of their corner of The Big Apple.