TRIBECA

Manhattan

Geographic Setting

Bounded by Canal Street to the north and Murray Street and Chambers Street to the south, extending from Broadway westward to the Hudson River, TriBeCa—an acronym for Triangle Below Canal Street—occupies a vast, low-rise expanse of Lower Manhattan that fuses industrial heritage with refined urban living. Once the city’s produce and dry-goods hub, it is now one of the most architecturally cohesive and artistically revered neighborhoods in New York.

The district’s cobblestone streets—Hudson, Greenwich, West Broadway, Franklin, and Duane—weave through a landscape of 19th-century warehouses and lofts converted into spacious residences, galleries, and studios. To the west, manicured piers and parkland along the Hudson River Greenway provide panoramic waterfront views; to the east, Broadway marks the threshold to SoHo and Civic Center. With its cast-iron façades, brick warehouses, and generous proportions, TriBeCa embodies both the physical solidity of New York’s mercantile past and the quiet prestige of its creative present.

Etymology and Origins

The name TriBeCa—a contraction of Triangle Below Canal—was coined in the 1970s by city planners and real-estate surveyors mapping zoning districts in Lower Manhattan. But the area’s history extends back over two centuries. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, this land lay just north of Colonial New York’s Common Lands and west of the original Collect Pond, which had been filled in by 1811. As landfill extended the shoreline westward, wharves and warehouses rose along Washington Street and Greenwich Street, making the district a vital link in the city’s maritime trade network.

The triangle’s earliest identity was practical rather than poetic—an industrial grid serving the Hudson River piers. Yet from its inception, TriBeCa was defined by structure, craftsmanship, and commerce—qualities that would later form the foundation of its artistic and residential rebirth.

The Neighborhood

19th Century: The Warehouse Era and Mercantile Grandeur

By the mid-1800s, TriBeCa had become the principal commercial quarter of New York’s expanding harbor economy. The Erie Canal (completed 1825) and the advent of steam shipping transformed Lower Manhattan into the logistical heart of the young nation. TriBeCa’s wide cobbled streets and sturdy masonry buildings were designed for freight wagons, goods exchange, and river access.

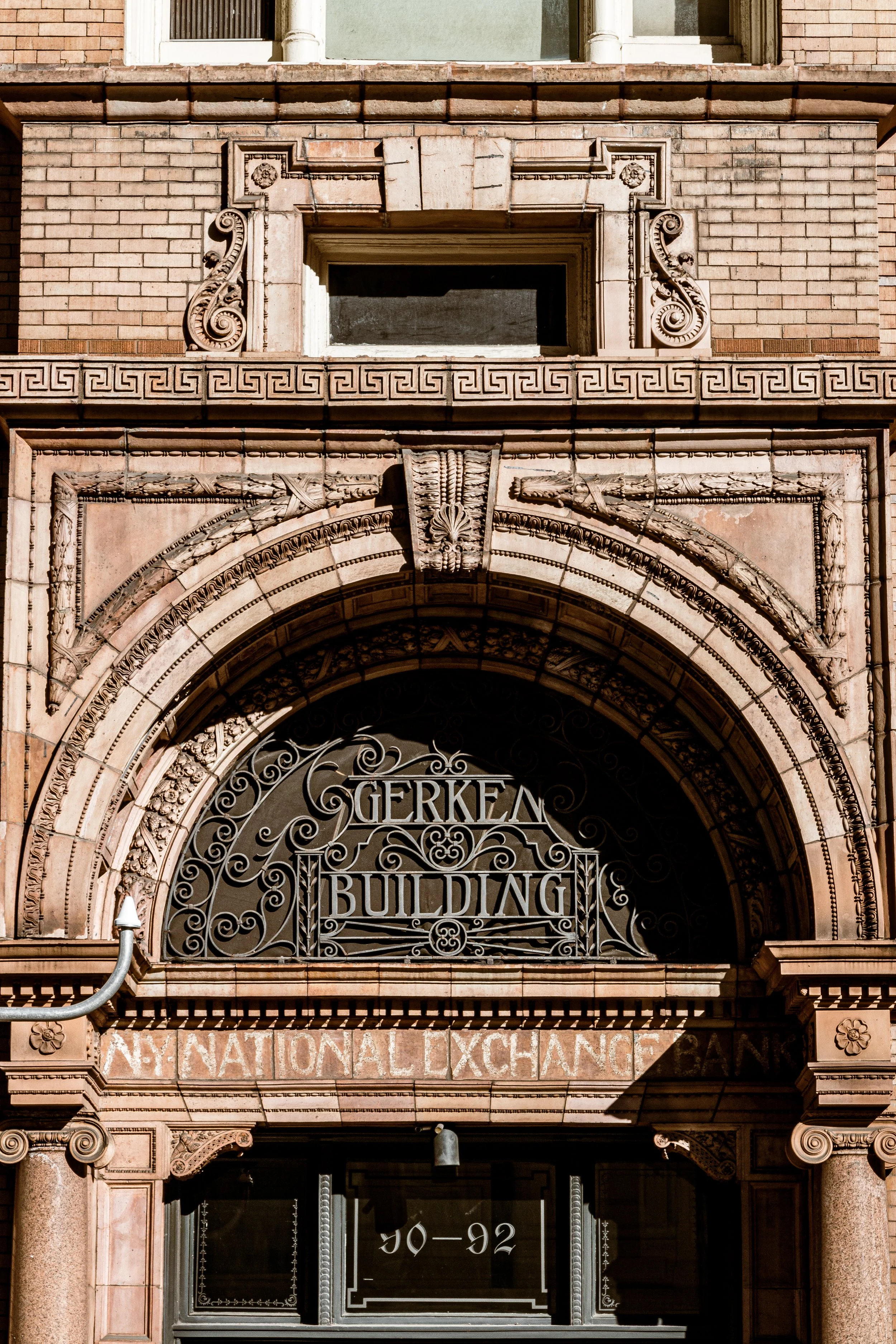

Architects such as Griffith Thomas, James Bogardus, and Henry Fernbach created loft and warehouse structures whose cast-iron and brick façades combined durability with ornament. The Romanesque Revival, Italianate, and Second Empire styles dominated—cornices, pilasters, and arched windows lending elegance to utilitarian forms. The New York Mercantile Exchange Building and Coffee and Cotton Exchanges, along with wholesale grocers and dry-goods firms, gave the area its nickname: the “produce district.”

By the late 19th century, TriBeCa’s economy thrived on proximity to the Washington Market, the largest wholesale food market in the United States. Its brick sheds and bustling carts filled Greenwich, Murray, and Duane Streets with daily clamor. The neighborhood’s built environment—spacious interiors with high ceilings and loading bays—was engineered for trade and industry, yet imbued with architectural grace. These very features would, decades later, make TriBeCa irresistible to artists seeking space and light.

Early–Mid 20th Century: Industry, Decline, and Transition

In the early 20th century, TriBeCa remained an industrial powerhouse. Warehouses stored textiles, butter, coffee, and produce from across the world. The elevated trains along Greenwich Street (1870s–1940) and the construction of the Holland Tunnel (opened 1927) reinforced the district’s logistical role, linking Manhattan’s port to New Jersey’s freight lines.

However, the rise of refrigeration, trucking, and container shipping after World War II rendered the old warehouses obsolete. The once-thriving Washington Market declined rapidly as the Fulton Fish Market and larger Bronx distribution centers replaced it. By the 1960s, many buildings stood vacant; cobblestones were broken, and the air of commerce gave way to silence.

Yet within that quiet, a new community emerged. Like SoHo to the north, TriBeCa’s vast, affordable lofts attracted painters, sculptors, and photographers seeking workspace. Artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, Marisol Escobar, and Richard Serra found in its industrial geometry both scale and solitude. The area’s emptiness became its muse.

TriBeCa Photographic Tour

1970s–1980s: The Artist Colonization and Historic Preservation

The 1970s marked the birth of modern TriBeCa as an artistic and architectural landmark. The neighborhood’s name entered common usage through real-estate zoning documents and was adopted by artists and preservationists seeking to define their community. Pioneers renovated abandoned warehouses into live–work lofts, laying bare the iron columns and brick arches that defined the industrial aesthetic.

In 1976, the Landmarks Preservation Commission designated four TriBeCa Historic Districts, protecting more than 60 blocks of 19th-century architecture. This early preservation effort—one of the most comprehensive in the city—ensured that TriBeCa’s transformation would respect its industrial past. Galleries, performance spaces, and experimental venues followed: The Mudd Club (1978) on White Street became a crucible of punk, new wave, and conceptual art, while independent filmmakers and musicians found an urban stage amid the cobblestones.

By the 1980s, TriBeCa had become a byword for downtown sophistication—gritty yet refined, historical yet avant-garde. The TriBeCa Film Festival, founded later in 2002, would formalize the creative legacy that began in these decades.

Late 20th–21st Century: From Artistic Frontier to Urban Haven

By the 1990s, TriBeCa completed its metamorphosis into one of New York’s most desirable residential districts. Loft conversions became luxury condominiums, and former factories transformed into high-end apartments and boutique offices. The Hudson River Park, developed in the 2000s, turned the derelict piers west of West Street into promenades, playgrounds, and green spaces—reconnecting the neighborhood to the waterfront it had once served industrially.

The TriBeCa Film Festival, established by Robert De Niro, Jane Rosenthal, and Craig Hatkoff in 2002, in response to the September 11 attacks, reasserted the area’s identity as a creative and civic hub. Each spring, it brings international audiences to its streets and reinforces TriBeCa’s role as a beacon of resilience and cultural exchange.

Today, the district balances preservation and innovation. Landmarked 19th-century facades stand beside discreetly modern buildings such as 56 Leonard Street—a sculptural tower by Herzog & de Meuron nicknamed the “Jenga Building.” Michelin-starred restaurants, design studios, and media firms fill its historic blocks, yet the neighborhood’s pace remains measured and residential. Children play on Duane Park’s lawns; the aroma of coffee drifts from corner cafés; and the hum of the Hudson carries through open loft windows.

TriBeCa Photo Gallery

Spirit and Legacy

TriBeCa’s legacy is transformation without erasure—a neighborhood that has evolved from commerce to culture while preserving its essential form and soul. It is a landscape of continuity: cast-iron columns still support new lives; cobblestones once worn by freight carts now echo with footsteps of artists, families, and filmmakers.

The district stands as proof that adaptive reuse can elevate the past into the present without loss of integrity. Its spirit—creative, composed, and quietly self-assured—captures the mature phase of downtown New York: the moment when industry gave way to imagination, and imagination, in turn, built a new civic pride.

New York City

Use this custom Google map to explore where every neighborhood in all five boroughs of New York City is located.

The Five Boroughs

One of New York City’s unique qualities is its organization in to 5 boroughs: Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, The Bronx, and Staten Island. These boroughs are part pragmatic administrative districts, and part vestiges of the region’s past. Each borough is an entire county in New York State - in fact, Brooklyn is, officially, Kings County, while Staten Island is, officially Richmond County. But that’s not the whole story …

Initially, New York City was located on the southern tip of Manhattan (now the Financial District) that was once the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. Across the East River, another city was rising: Brooklyn. In time, the city planners realized that unification between the rapidly rising cities would create commercial and industrial opportunities - through streamlined administration of the region.

So powerful was the pull of unification between New York and Brooklyn that three more counties were pulled into the unification: The Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island. And on January 1, 1898, the City of New York unified two cities and three counties into one Greater City of New York - containing the five boroughs we know today.

But because each borough developed differently and distinctly until unification, their neighborhoods likewise uniquely developed. Today, there are nearly 390 neighborhoods, each with their own histories, cultures, cuisines, and personalities - and each with residents who are fiercely proud of their corner of The Big Apple.