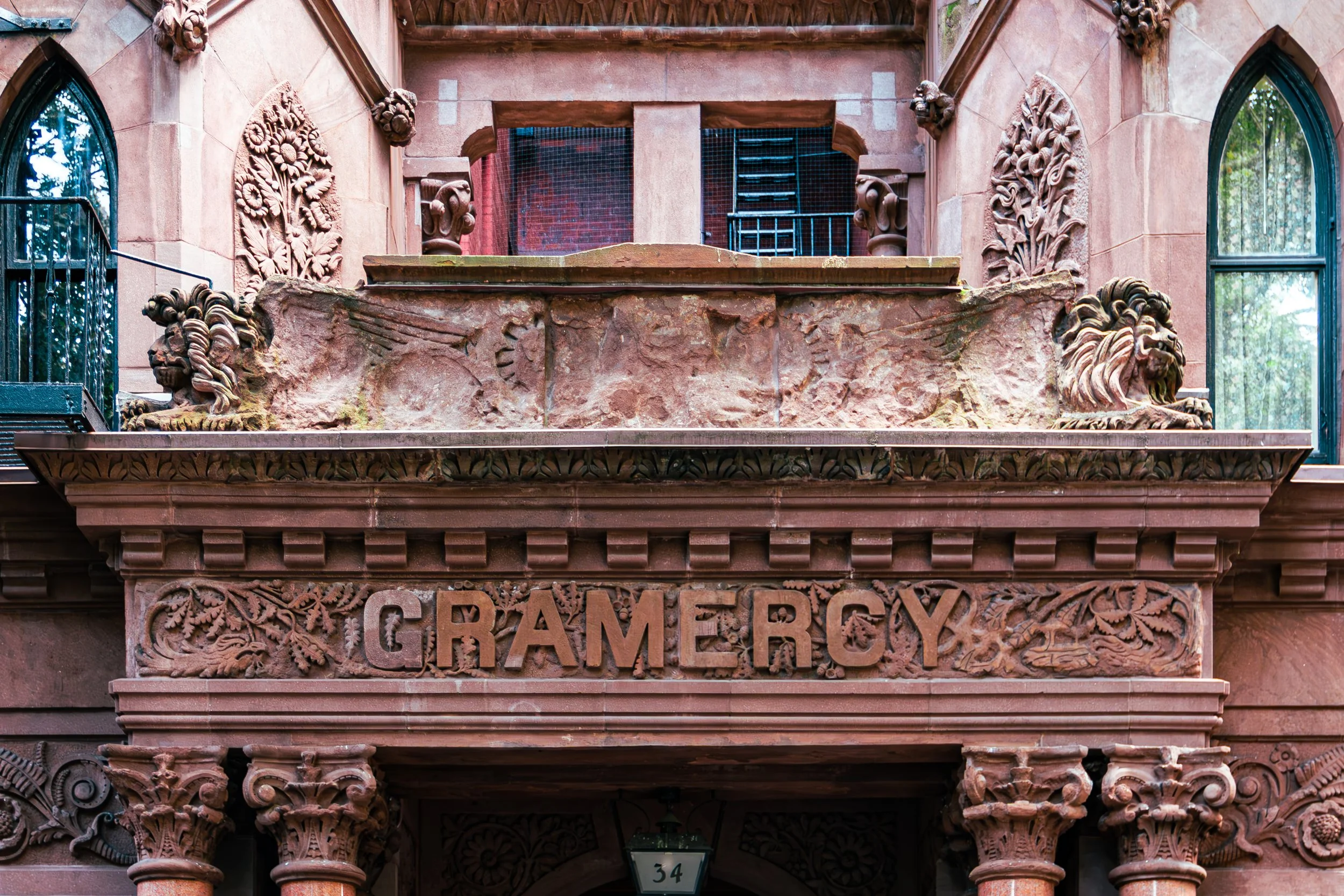

GRAMERCY

Geographic Setting

Nestled between 14th and 23rd Streets, and Park Avenue South and Third Avenue, Gramercy occupies one of the most tranquil and distinguished enclaves in Manhattan. Its heart is Gramercy Park, a verdant, gated square that remains the only private park in the borough — an emerald sanctuary amid the city’s perpetual motion. The neighborhood’s calm, tree-lined blocks stand in poetic contrast to the bustle of Union Square to the south and the commercial grid of Midtown to the north. Though small in scale, Gramercy’s influence on New York’s architectural, literary, and civic identity has been immense — a pocket of refinement that has preserved the 19th century’s ideal of urban grace into the modern age.

Etymology and Origins

The name Gramercy derives from the Dutch phrase Krom Moerasje, meaning “crooked little swamp.” The area, once a marshy expanse of ponds and streams, lay beyond the city’s early grid and remained largely undeveloped until the 1830s. When developer Samuel B. Ruggles purchased the land in 1831, he envisioned something radical for New York: a planned residential square modeled after the private garden squares of London.

Ruggles drained the swamp, laid out elegant plots around a central park, and deeded the park’s ownership collectively to the surrounding property owners — a civic innovation that guaranteed its preservation in perpetuity. The design, formalized in 1832, gave rise to Gramercy Park, and by extension, to the neighborhood that would inherit its name and ethos.

The Neighborhood

19th Century: The Birth of a Civic Ideal

By the 1840s, Gramercy Park had become one of Manhattan’s most desirable addresses. Brownstones and Greek Revival townhouses framed the park’s wrought-iron gates, their façades restrained but dignified. The National Academy of Design and the Players Club, founded in 1888 by actor Edwin Booth, gave the square its artistic and intellectual gravitas.

Ruggles’s vision extended beyond aesthetics — he saw the park as a civic experiment in community stewardship. Access was limited to keyholders, ensuring that residents collectively maintained the park’s landscape and moral order. The result was both egalitarian and exclusive, embodying the 19th-century belief that beauty could inspire virtue.

By the Civil War era, the surrounding streets — particularly Irving Place and Lexington Avenue — had filled with genteel rowhouses, small hotels, and literary salons. Washington Irving, for whom Irving Place is named, lived nearby and lent the area his romantic sensibility. The neighborhood became a haven for writers, artists, and reformers drawn to its equilibrium of privacy and proximity.

Late 19th–Early 20th Century: Literature, Architecture, and Reform

The turn of the century brought a golden age to Gramercy’s cultural life. The National Arts Club, established in 1898 in the former Tilden Mansion at 15 Gramercy Park South, became a meeting ground for painters, poets, and architects. Its stained-glass windows and carved oak interiors embodied the Arts and Crafts movement’s ideals of craftsmanship and integrity.

On the opposite side of the park, the Players Club became an equally storied institution — a gathering place for actors, playwrights, and intellectuals including Mark Twain, Laurence Hutton, and John Barrymore. Together, these institutions established Gramercy as a cultural precinct that bridged New York’s artistic and civic spheres.

Architecturally, the neighborhood diversified during this period. Italianate, Gothic Revival, and Beaux-Arts apartments replaced some early brownstones, yet the overall scale remained human and harmonious. The Gramercy Park Hotel, opened in 1925, became an instant landmark — a red-brick bastion of old-world charm that would later host generations of artists, musicians, and dignitaries.

Beyond the park, Gramercy’s influence radiated through civic reform. Peter Cooper, whose Cooper Union opened nearby in 1859, embodied the district’s philanthropic spirit, offering free education to all regardless of gender or class. Theodore Roosevelt, born just north on East 20th Street, carried Gramercy’s civic idealism into the White House.

Mid-20th Century: Preservation and Persistence

While much of Manhattan succumbed to high-rise development in the mid-20th century, Gramercy largely resisted. Residents and civic groups worked to preserve the neighborhood’s architectural integrity, culminating in the 1966 designation of the Gramercy Park Historic District — one of the city’s earliest. This status protected not only the facades but the character of the streets: the quiet rhythm of stoops, the dappled shade of sycamores, and the low murmur of evening conversation through open windows.

During these decades, Gramercy retained its air of quiet dignity even as surrounding districts modernized. The Irving Place Tavern, the Pete’s Tavern (established 1864), and the Salvation Army’s Parkside Residence became neighborhood fixtures. Writers such as O. Henry and John Dos Passos found inspiration in its calm — the sense that, within a city of upheaval, Gramercy remained a pocket of equilibrium.

Late 20th–21st Century: Revival and Reflection

By the late 20th century, Gramercy experienced a subtle renaissance. Restoration of historic buildings, renewed investment, and the revival of nearby Union Square brought fresh vitality. The Gramercy Park Hotel, reimagined by Julian Schnabel in the 2000s, combined bohemian art with timeless luxury, reaffirming the neighborhood’s dual identity as both refuge and creative crucible.

In the 21st century, Gramercy stands as one of the city’s most meticulously preserved neighborhoods. Its streets remain lined with ivy-draped townhouses and stately prewar co-ops. The Park’s iron gates, still accessible only by keyholders, lend an aura of secrecy, yet the surrounding sidewalks teem with café life, conversation, and a quiet cosmopolitanism.

Though bounded by stone, Gramercy feels alive — a living organism whose beauty depends not on nostalgia but on care. Its success lies in balance: the coexistence of privacy and openness, heritage and evolution.

Architecture and Atmosphere

Architecturally, Gramercy is a masterclass in proportion and restraint. The Greek Revival brownstones of the 1840s remain intact along the park’s perimeter, their doorways framed by Ionic pilasters. Later additions — Beaux-Arts apartments, neo-Gothic churches, and Italianate mansions — complement rather than overwhelm. The effect is one of deliberate harmony, where no building shouts but each contributes to a collective elegance.

The atmosphere is hushed but never sterile. Mornings bring sunlight filtering through elm leaves onto brick façades; afternoons fill with the murmur of conversation outside cafés on Irving Place. At twilight, as the lamps within Gramercy Park flicker to life, the neighborhood seems to glow from within — a small republic of civility in a restless city.

Spirit and Legacy

Gramercy’s legacy is stewardship — the idea that beauty, once created, must be tended with discipline and love. It stands as proof that refinement need not mean exclusion, and that a city’s vitality can coexist with serenity.

New York City

Use this custom Google map to explore where every neighborhood in all five boroughs of New York City is located.

The Five Boroughs

One of New York City’s unique qualities is its organization in to 5 boroughs: Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, The Bronx, and Staten Island. These boroughs are part pragmatic administrative districts, and part vestiges of the region’s past. Each borough is an entire county in New York State - in fact, Brooklyn is, officially, Kings County, while Staten Island is, officially Richmond County. But that’s not the whole story …

Initially, New York City was located on the southern tip of Manhattan (now the Financial District) that was once the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. Across the East River, another city was rising: Brooklyn. In time, the city planners realized that unification between the rapidly rising cities would create commercial and industrial opportunities - through streamlined administration of the region.

So powerful was the pull of unification between New York and Brooklyn that three more counties were pulled into the unification: The Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island. And on January 1, 1898, the City of New York unified two cities and three counties into one Greater City of New York - containing the five boroughs we know today.

But because each borough developed differently and distinctly until unification, their neighborhoods likewise uniquely developed. Today, there are nearly 390 neighborhoods, each with their own histories, cultures, cuisines, and personalities - and each with residents who are fiercely proud of their corner of The Big Apple.