EAST HARLEM

Manhattan

Geographic Setting

Situated in the northeastern reaches of Manhattan, East Harlem occupies the expanse between East 116th Street and East 143rd Street, bounded by Fifth Avenue to the west and the Harlem River to the east. This terrain, rising gently from Central Park’s northern edge to the bridges that cross into the Bronx, forms a landscape of long avenues, redbrick towers, and resilient communities. The neighborhood’s western boundary at Fifth Avenue faces the monumental stretch of Museum Mile, while its eastern edge meets the rhythmic hum of the FDR Drive and the steel arcs of the Madison Avenue and Third Avenue Bridges.

Within these bounds lies a district layered with New York’s social, architectural, and demographic evolution—a community forged through waves of immigration and urban change, defined as much by its strength of identity as by its geography. Although often conflated with Spanish Harlem (El Barrio) to the south, East Harlem north of 116th Street has its own distinct trajectory, one rooted in older European settlements, 20th-century public housing reforms, and a steady intermingling of cultural groups that continues to shape its modern voice.

Etymology and Origins

The term “East Harlem” first gained currency in the late 19th century, when the area emerged as a northern extension of Harlem proper—then the city’s most fashionable suburb. The name simply described its position: east of Fifth Avenue, along the Harlem River. Yet the land’s history reaches back to the Dutch colonial period, when it formed part of the Nieuw Haarlem settlement founded in 1658 under Governor Peter Stuyvesant. Early maps depict farms and orchards lining what would become Pleasant Avenue, First Avenue, and Harlem Lane (now St. Nicholas Avenue), with the Harlem River providing both boundary and lifeline.

For centuries, the area remained sparsely populated—its marshes and meadows interrupted by scattered estates. It was only with the arrival of the New York and Harlem Railroad (1830s) and later the elevated lines (1870s–1880s) that development advanced northward. By the end of the 19th century, East Harlem had transformed from farmland into a dense, mixed working-class neighborhood—one that would absorb successive generations of immigrants and become a crucible of urban American life.

The Neighborhood

Late 19th–Early 20th Century: Italian Harlem and the Urban Grid

Between 1880 and 1920, East Harlem became one of the largest Italian enclaves in the United States, earning the nickname “Italian Harlem.” Immigrants from Sicily, Calabria, and Naples settled along First Avenue, Pleasant Avenue, and the cross streets between 116th and 125th, drawn by affordable tenements and jobs in nearby factories and breweries. Church spires soon punctuated the skyline—Our Lady of Mount Carmel (1884) on East 115th Street being the most enduring landmark, around which the annual Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and its storied procession still take place.

As the Italian population spread northward beyond 116th Street, East Harlem developed its own identity distinct from the older, African American–dominated districts to the west. Its avenues became lined with bakeries, social clubs, and groceries where dialects from southern Italy mingled with the rhythms of the city. Figures such as Fiorello H. La Guardia, who grew up in the neighborhood and later became one of New York’s most beloved mayors, embodied its blend of ethnic pride and civic aspiration.

By the 1920s, East Harlem was also absorbing Jewish and Irish residents, creating a polyglot mix of tenement life. The elevated trains along Second and Third Avenues, casting their shadows across the blocks, gave the district both accessibility and its distinctive visual grit.

Mid-20th Century: Public Housing and Urban Change

The Depression and postwar decades transformed East Harlem more profoundly than any period before or since. Overcrowding, aging tenements, and economic hardship led to sweeping urban renewal. Beginning in the 1940s, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) undertook one of its largest concentrations of public housing projects in the borough here, replacing blocks of tenements with modernist “tower-in-the-park” developments.

Complexes such as the Wagner Houses (1958), East River Houses (1941), and Jefferson Houses (1959) redefined the neighborhood’s skyline and demographics. African American and Puerto Rican families moved into these developments in large numbers, while many Italian families relocated to the Bronx or suburbs. The construction of the FDR Drive (1940s) further reshaped the eastern edge, severing the community from the riverfront but providing new vistas of the Harlem River bridges.

Through these decades, East Harlem developed a distinct rhythm from Spanish Harlem (El Barrio) to the south. While El Barrio’s Puerto Rican and Latin cultural centers flourished below 116th Street, East Harlem north of it remained more demographically mixed—home to African Americans, Italians, and later growing Dominican, West African, and Mexican populations. Its institutions—The East Harlem Triangle, Union Settlement House, and the Harlem River Park Alliance—anchored a civic identity rooted in service, education, and community resilience.

East Harlem Photographic Video

Late 20th Century: Resilience and Renaissance

By the 1970s–1980s, East Harlem faced the familiar challenges of New York’s inner-city neighborhoods: economic disinvestment, crime, and population decline. Vacant lots dotted the avenues, and many of the once-proud Italian storefronts shuttered. Yet even amid hardship, cultural continuity endured. Churches such as Our Lady of Mount Carmel maintained processions and festivals that bridged generations; new community gardens reclaimed empty land; and housing cooperatives began the long process of neighborhood reinvestment.

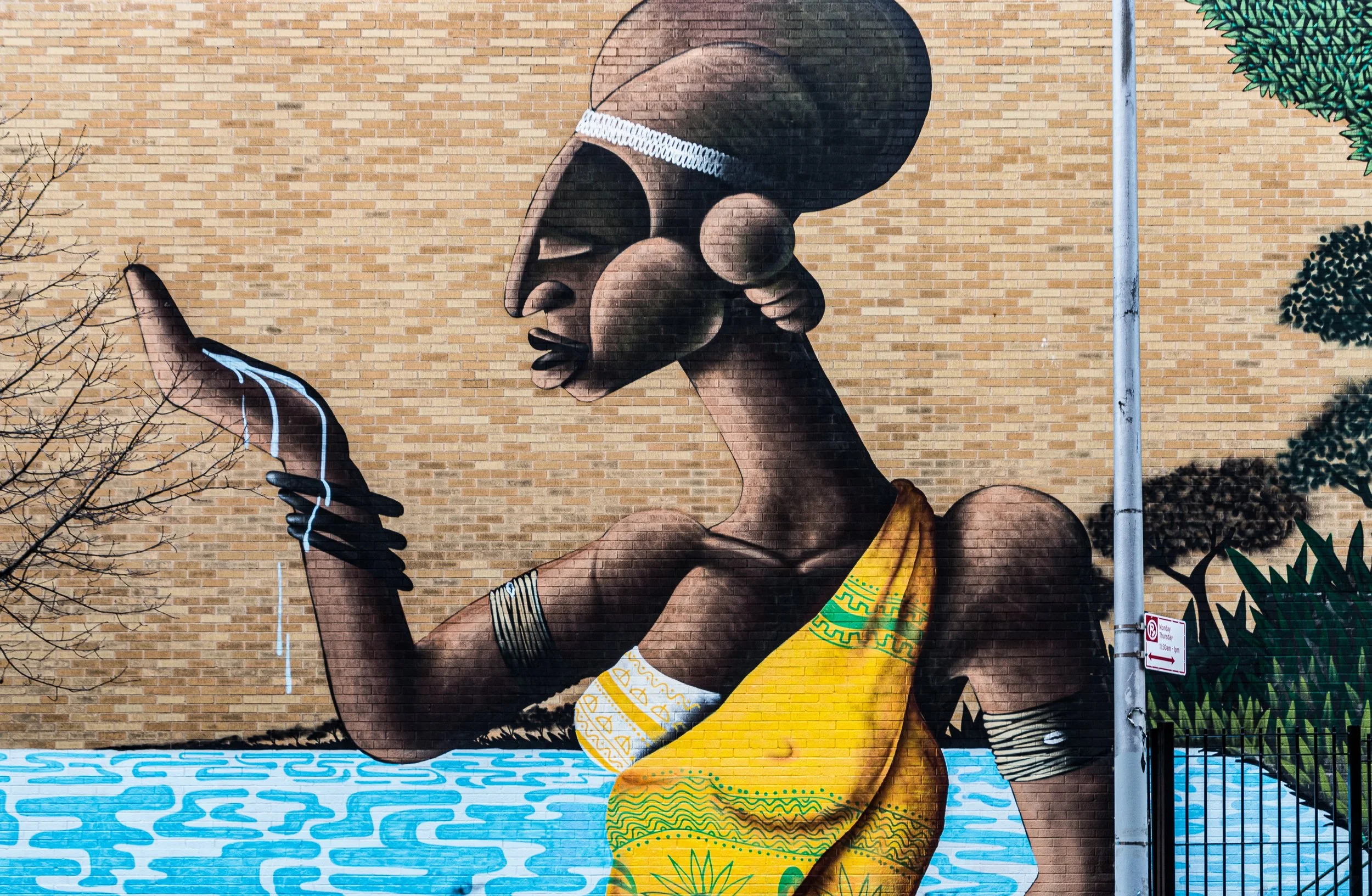

Grassroots organizations—Hope Community Inc., Union Settlement, and Little Sisters of the Assumption Family Health Service—played crucial roles in stabilizing the district. The Harlem River Drive Park and East 120th Street community gardens became green sanctuaries amid the concrete, while murals and public art began to reinterpret East Harlem’s history for a new era.

21st Century: Cultural Continuity and Emerging Change

In the 21st century, East Harlem has entered another phase of transformation. The expansion of Columbia University’s Harlem campus to the west, along with rezoning initiatives, has brought new investment and tension. Condominiums and charter schools have joined the landscape of public housing and century-old churches, reflecting both renewal and pressure.

Despite change, East Harlem north of 116th Street retains a community cohesion and rhythm distinct from its southern neighbor, El Barrio. While Spanish Harlem celebrates Latin identity and heritage, East Harlem reflects a layered mosaic—Italian, African American, Dominican, Mexican, and West African influences sharing the same grid. Pleasant Avenue, once the heart of Italian Harlem, remains lined with bakeries and annual festivals that honor that legacy, while newer markets along Third Avenue and Lexington Avenue reflect global diversity.

Redevelopment along the Harlem River waterfront, including parks and bike paths, has begun reconnecting the neighborhood to the river it long faced away from. Schools, health centers, and youth programs continue the social mission that has defined East Harlem for more than a century: to build strength through inclusion and endurance.

East Harlem Photo Gallery

Spirit and Legacy

East Harlem’s legacy is one of renewal through community. Its history mirrors New York’s larger story—immigration, displacement, adaptation—but with a continuity of spirit that transcends change. From the Italian processions along Pleasant Avenue to the community gardens blooming on reclaimed land, from the sound of church bells to the laughter from schoolyards along 120th Street, East Harlem endures as a place where identity is layered, not lost.

New York City

Use this custom Google map to explore where every neighborhood in all five boroughs of New York City is located.

The Five Boroughs

One of New York City’s unique qualities is its organization in to 5 boroughs: Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, The Bronx, and Staten Island. These boroughs are part pragmatic administrative districts, and part vestiges of the region’s past. Each borough is an entire county in New York State - in fact, Brooklyn is, officially, Kings County, while Staten Island is, officially Richmond County. But that’s not the whole story …

Initially, New York City was located on the southern tip of Manhattan (now the Financial District) that was once the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. Across the East River, another city was rising: Brooklyn. In time, the city planners realized that unification between the rapidly rising cities would create commercial and industrial opportunities - through streamlined administration of the region.

So powerful was the pull of unification between New York and Brooklyn that three more counties were pulled into the unification: The Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island. And on January 1, 1898, the City of New York unified two cities and three counties into one Greater City of New York - containing the five boroughs we know today.

But because each borough developed differently and distinctly until unification, their neighborhoods likewise uniquely developed. Today, there are nearly 390 neighborhoods, each with their own histories, cultures, cuisines, and personalities - and each with residents who are fiercely proud of their corner of The Big Apple.